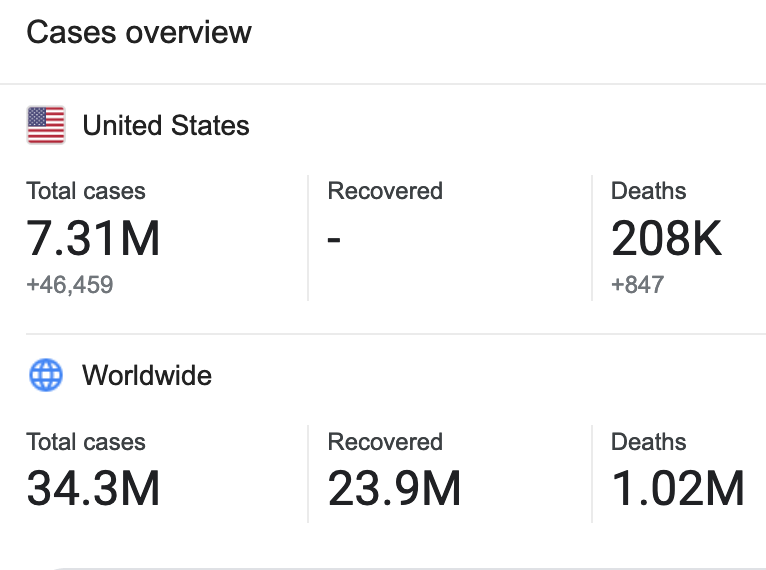

Crises reveal what organizations value. Whether a business demonstrates corporate responsibility during the COVID-19 pandemic, or fails to do so, can determine if the company and its leaders emerge from this crisis with the trust and confidence of their stakeholders intact.

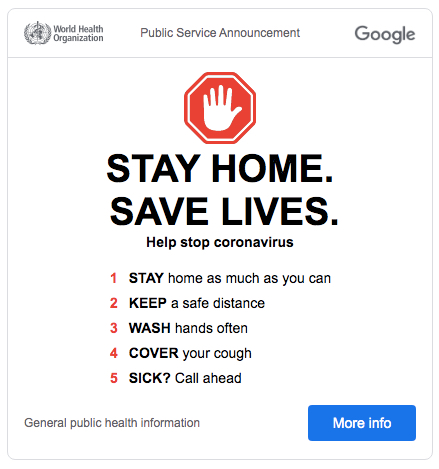

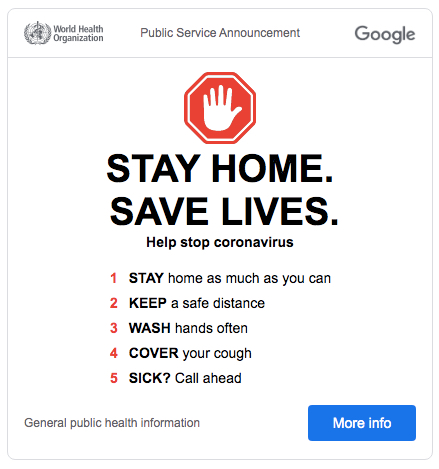

Source: google.com/covid19/

Definitions of corporate responsibility have evolved from an exclusive focus on shareholder returns, to the acknowledgment by businesses of a much broader group of corporate stakeholders and range of responsibilities. Acting responsibly today means more than legal compliance and goes beyond corporate philanthropy.

At its core, corporate responsibility means meeting stakeholder expectations for responsible conduct. Meeting both the financial and non-financial expectations of its investors, customers, employees, business partners, suppliers, regulators, and the communities where it operates, helps a company to manage risk, protect its reputation, attract and retain employees, grow its markets, and sustain its financial performance.

Demonstrating corporate responsibility is a key challenge for business leaders in the best of times. As my colleague Helio Fred Garcia observes, the COVID-19 crisis comprises simultaneous crises (public health, business, economic, information, governance, social, mental health) of unprecedented scope that require a multi-dimensional leadership response. [1]

Unprecedented in its scope, the COVID-19 pandemic is an opportunity for companies and their leaders to live their values by acting responsibly.

When navigating next steps during the pandemic, business leaders should keep in mind key principles for demonstrating corporate responsibility.

Understand the potential impacts of your crisis response.

Responsible organizations understand the potential impacts of their actions and take steps to “do no harm.” Business leaders determining how to respond to the pandemic need to assess the potential impacts on all company stakeholders.

Well-managed organizations plan for foreseeable crises. Companies that engage in meaningful crisis planning likely had a standby pandemic crisis plan they could draw upon as they began to address COVID-19. Effective crisis management plans identify potentially affected stakeholders and catalogue relevant corporate policies for high priority scenarios. A global manufacturer’s pandemic planning, for example, would have considered the business impact of supply chain interruptions, triggers to suspend executive travel, and criteria for allowing employees to work remotely.

When evaluating next steps, companies should seek to “do no harm” by preventing or mitigating harmful impacts.

Companies without a pandemic crisis plan in place can still identify potential impacts to guide their response. Enterprise-wide impact mapping and assessment can help an organization prioritize next steps. By applying a human rights impact lens to its operations and stakeholders, [2] a hospital system, for example, might prioritize securing adequate personal protective equipment to ensure the health and safety of its healthcare workers; expanding diagnostic testing among vulnerable communities to ensure nondiscrimination in patient access to healthcare, and communicating information about the virus and medical capacity to ensure public access to reliable and timely information.

Companies without a pandemic crisis plan in place can still identify potential impacts to guide their response. Enterprise-wide impact mapping and assessment can help an organization prioritize next steps. By applying a human rights impact lens to its operations and stakeholders, [2] a hospital system, for example, might prioritize securing adequate personal protective equipment to ensure the health and safety of its healthcare workers; expanding diagnostic testing among vulnerable communities to ensure nondiscrimination in patient access to healthcare, and communicating information about the virus and medical capacity to ensure public access to reliable and timely information.

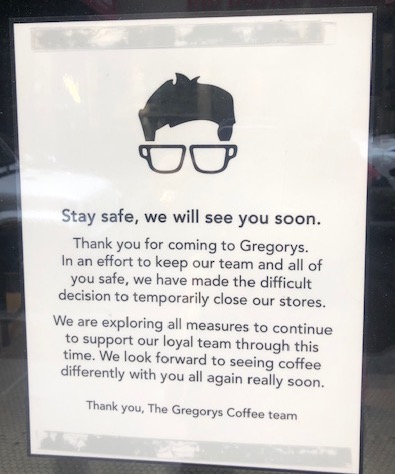

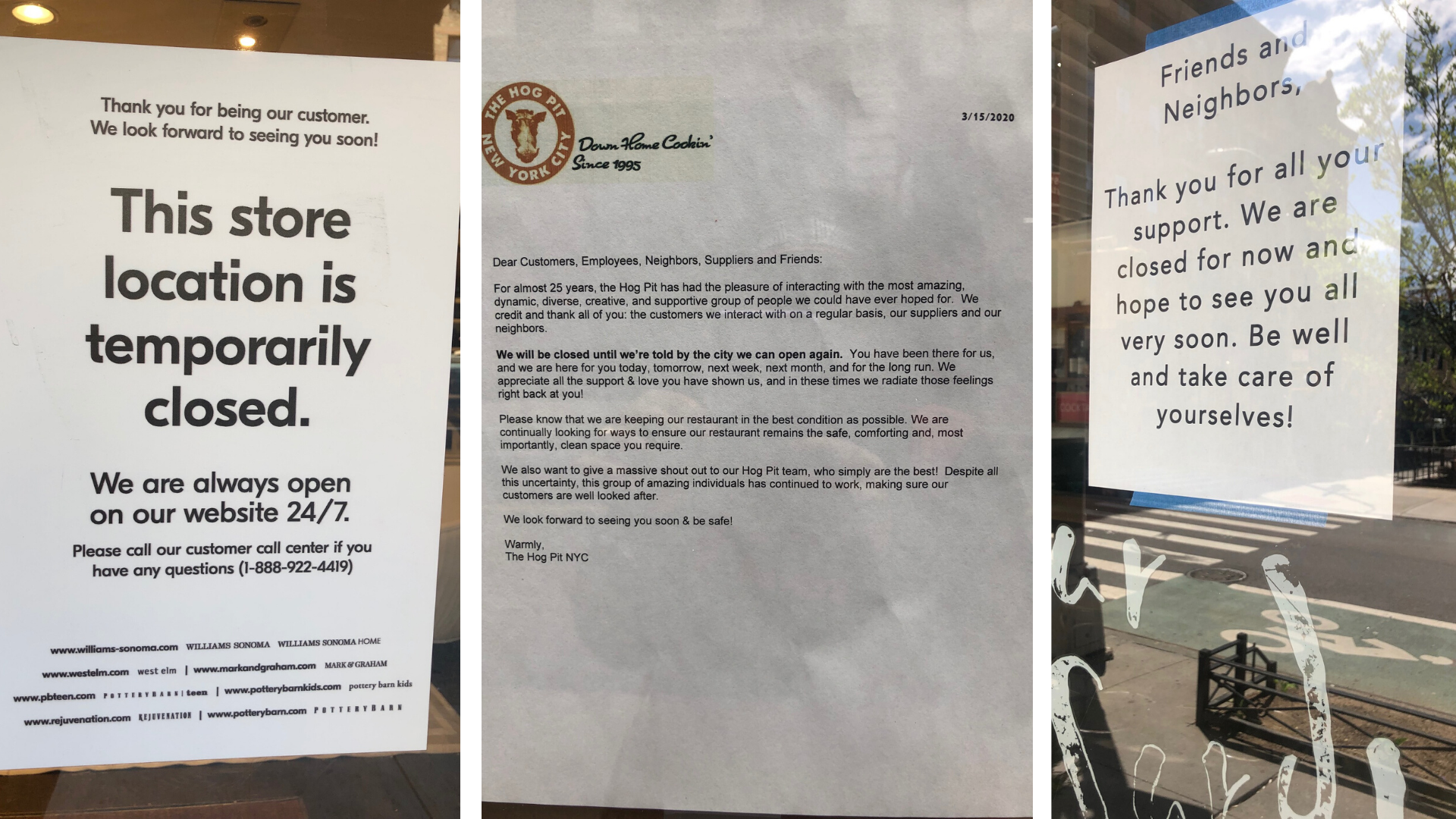

When evaluating next steps, companies should seek to “do no harm” by preventing or mitigating harmful impacts. Apparel companies that have cancelled supplier contracts for goods during the pandemic face criticism for triggering layoffs of the factory workers worldwide that make their products, often among the groups most vulnerable to COVID-19. A quick stakeholder impact assessment would have flagged the risk of harming supply chain workers. Responsible international brands have sought to protect workers by honoring their supplier contracts during the pandemic.

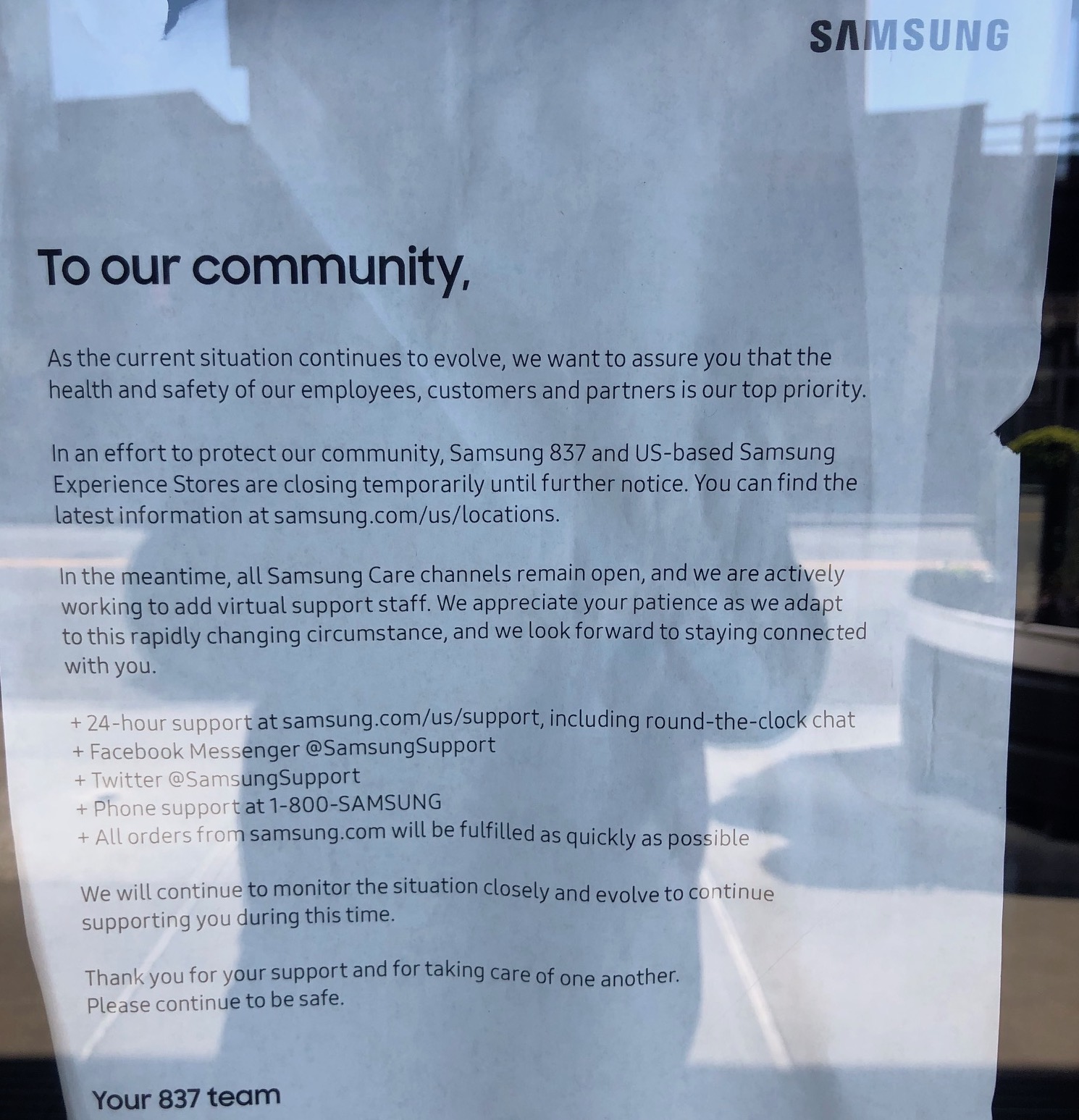

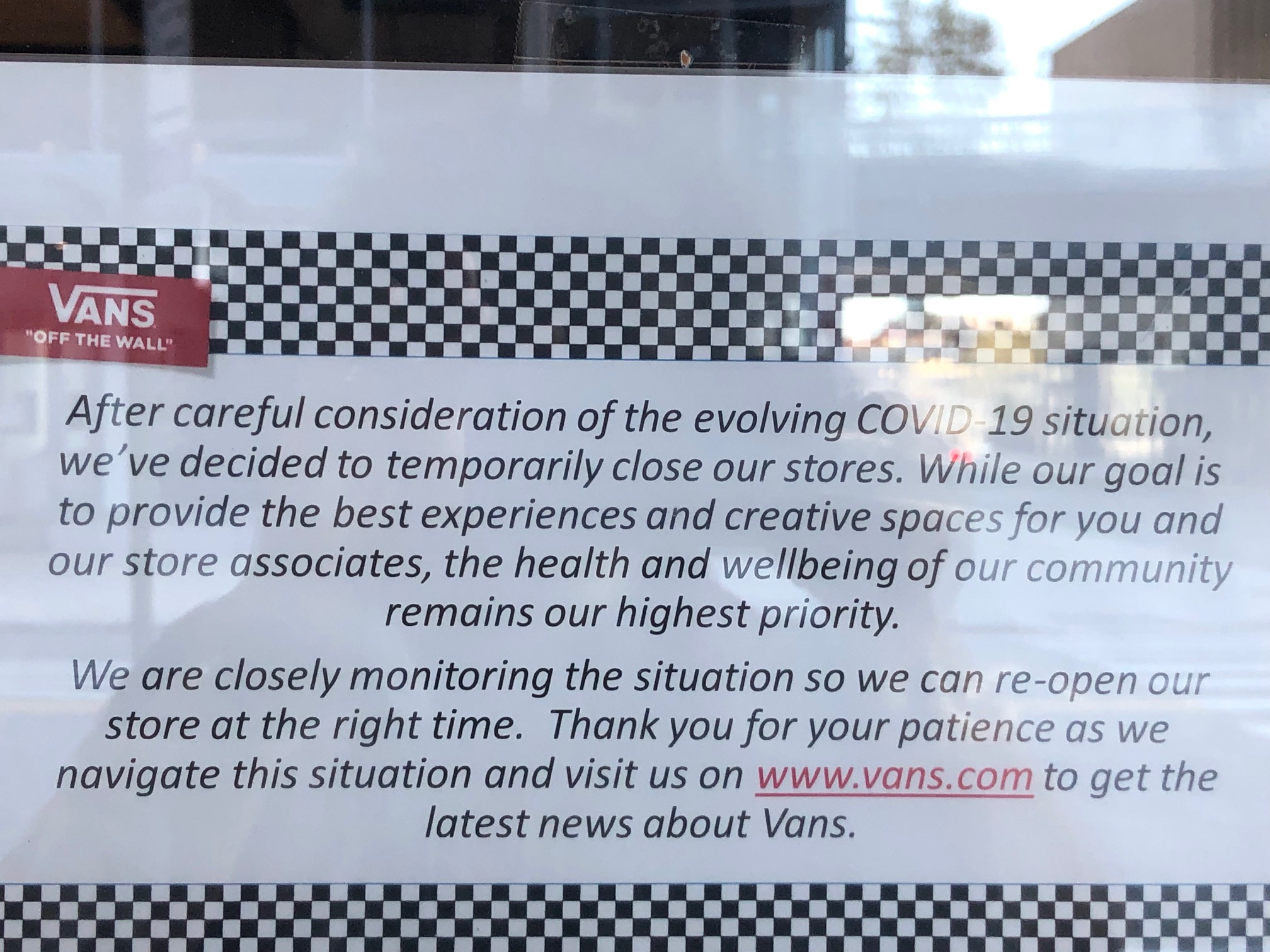

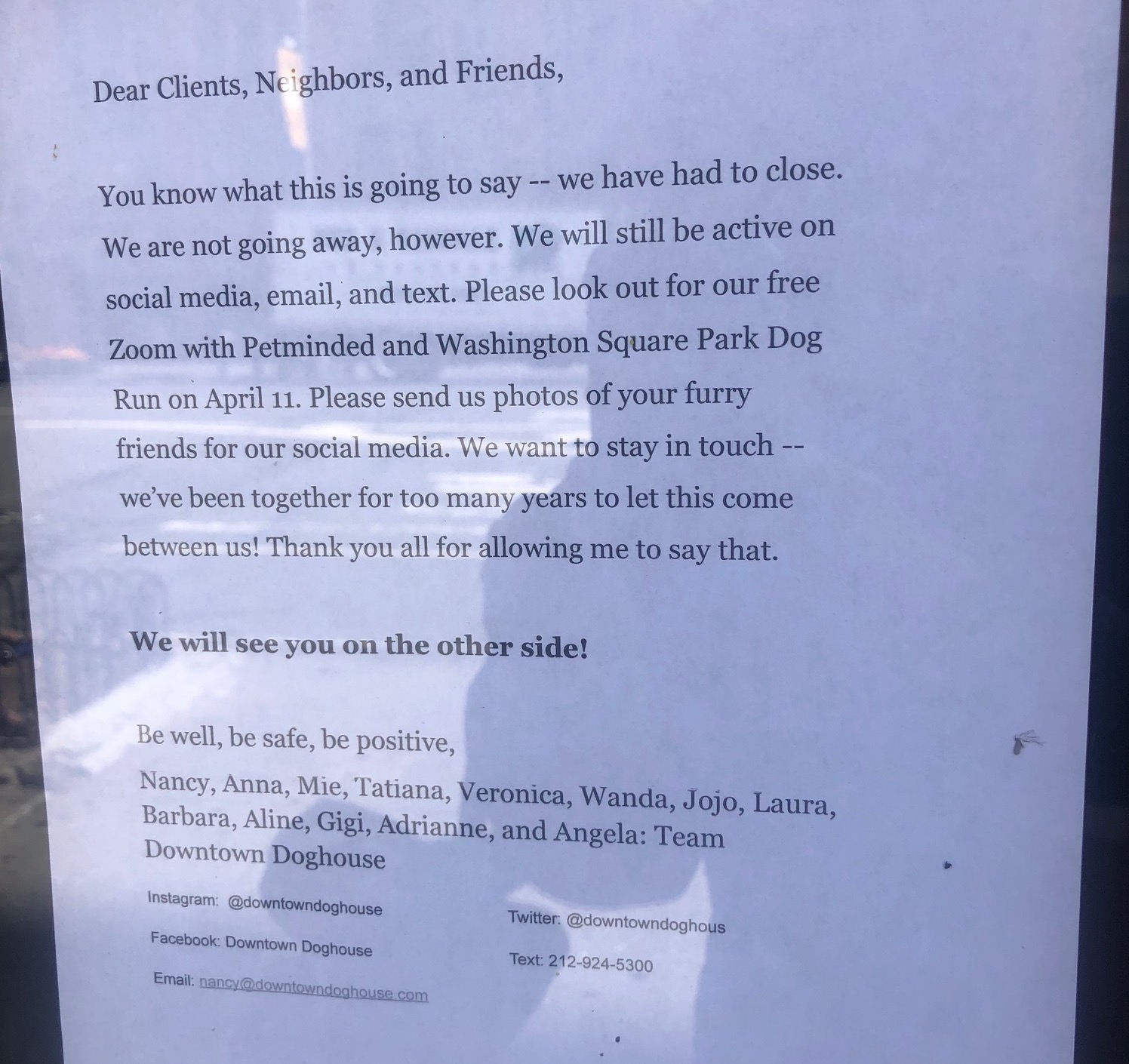

Similarly, companies that provide paid sick leave are protecting the health of employees, customers and the general public alike. When the California-based retailer Patagonia voluntarily closed its stores nationwide while continuing to pay its employees, its CEO and President, Rose Marcario stated, “It’s everyone’s responsibility to help stop the spread of this virus.”

Similarly, companies that provide paid sick leave are protecting the health of employees, customers and the general public alike. When the California-based retailer Patagonia voluntarily closed its stores nationwide while continuing to pay its employees, its CEO and President, Rose Marcario stated, “It’s everyone’s responsibility to help stop the spread of this virus.”

“It’s everyone’s responsibility to help stop the spread of this virus.”

− Rose Marcario, CEO and President, Patagonia Inc.

Anticipate changing stakeholder expectations.

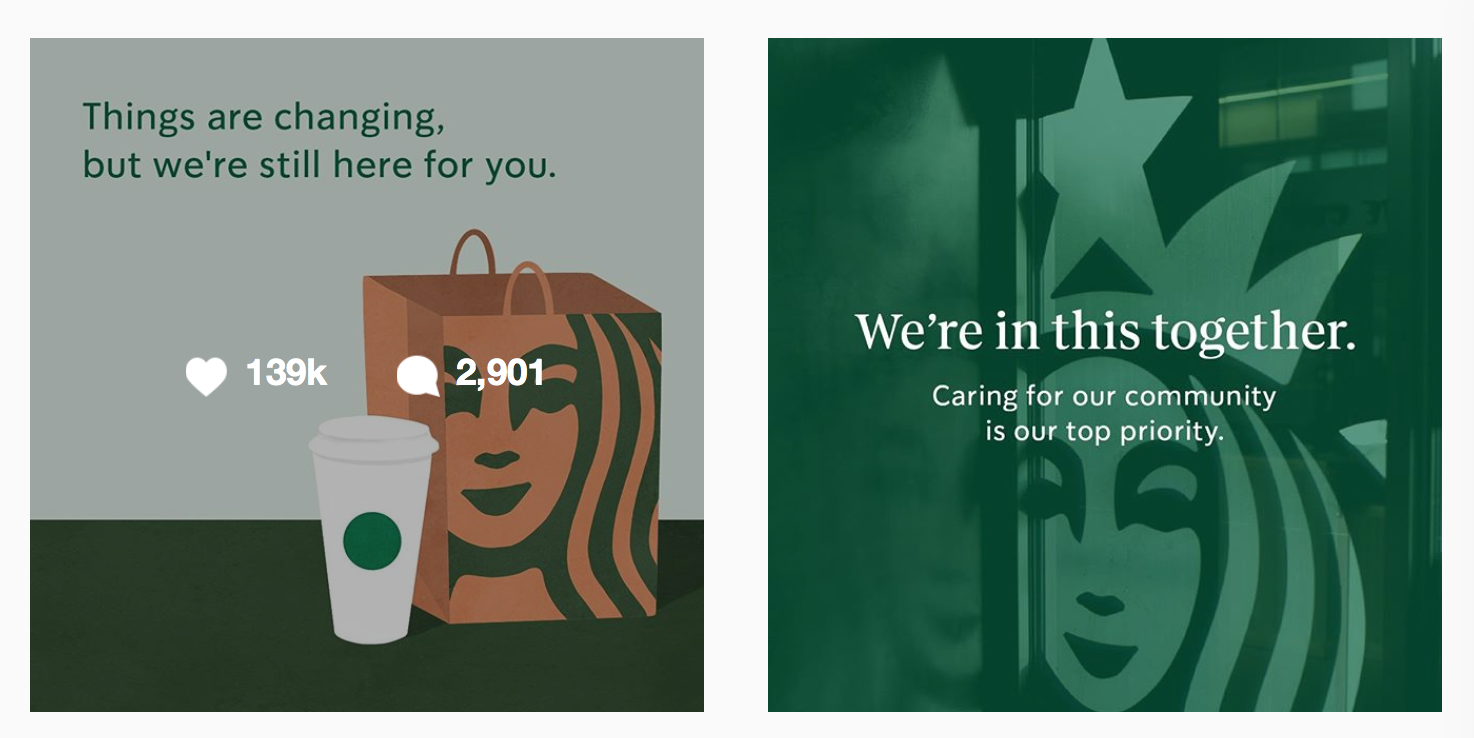

Meeting stakeholder expectations demonstrates corporate responsibility and earns the trust of those who matter most to your business. All stakeholders expect a responsible organization to care about the multiple dimensions of the COVID-19 crisis and to take appropriate action.

What stakeholders expect a responsible company to do will change. The current pandemic is a dynamic situation that calls for decision-makers to adapt policies to new information. Responsible companies meet stakeholders where they are and adjust accordingly.

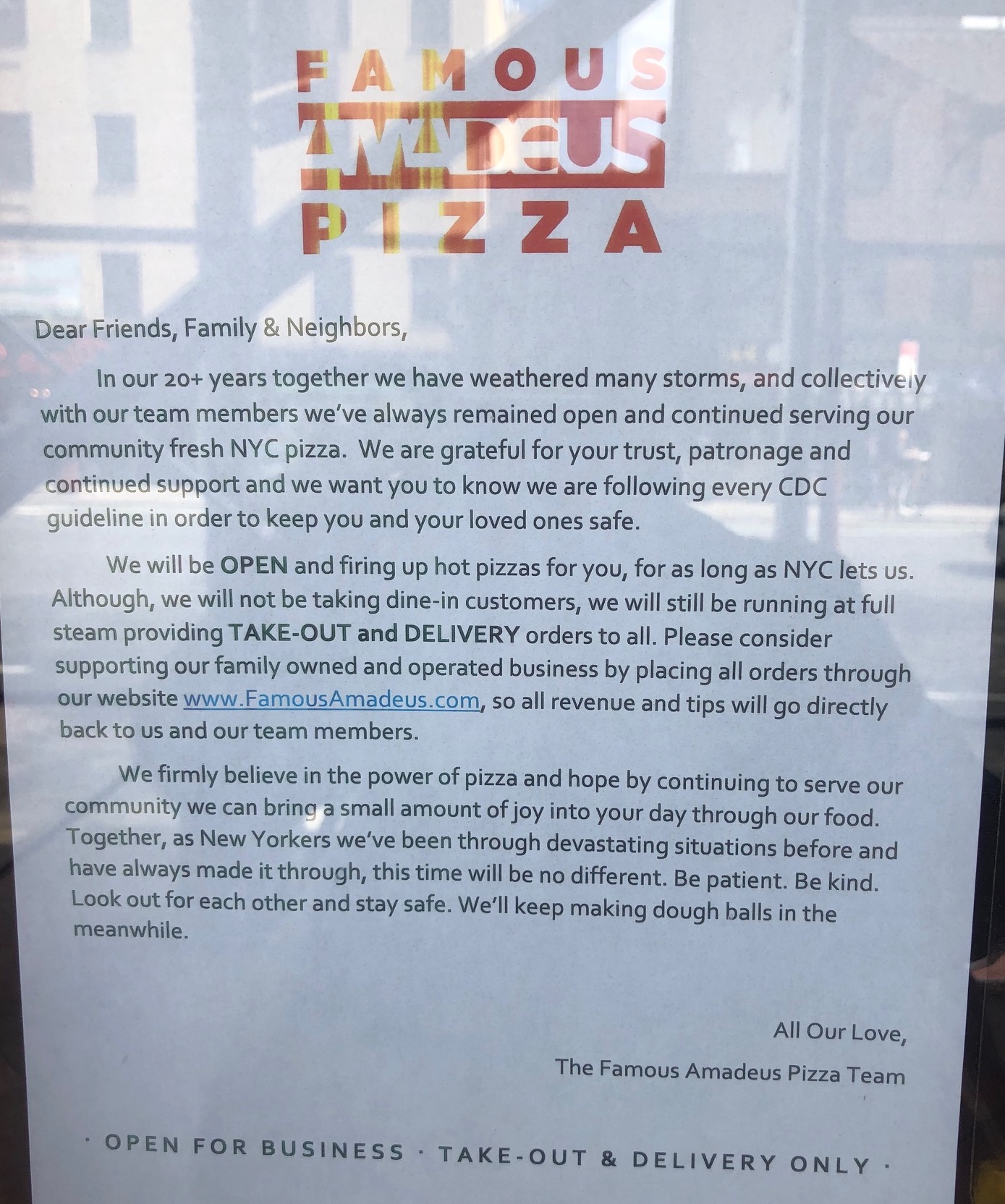

Customers, for example, expect essential businesses that remain open (or that reopen) to follow public health guidelines, to protect their employees, and to protect vulnerable community members. Obeying the law is the just the starting point.

On my first trip to the grocery store after a statewide “stay-at-home” order had been issued, the store had placed limits on the number of scarce items that customers could buy, like cleaning products and milk. Employees were working hard to keep shelves stocked. Two weeks later, consistent with evolving public health guidance, the store was limiting the number of customers allowed inside at once, plexiglass shields had been placed between checkout workers and customer payment stations, and all store employees wore gloves and masks. The grocery chain had also adopted an industry-wide practice reserving its opening hour for elderly customers. On my most recent shopping trip, the store had instituted “one-way” aisles to ensure physical distancing and all customers were required to wear face coverings.

On my first trip to the grocery store after a statewide “stay-at-home” order had been issued, the store had placed limits on the number of scarce items that customers could buy, like cleaning products and milk. Employees were working hard to keep shelves stocked. Two weeks later, consistent with evolving public health guidance, the store was limiting the number of customers allowed inside at once, plexiglass shields had been placed between checkout workers and customer payment stations, and all store employees wore gloves and masks. The grocery chain had also adopted an industry-wide practice reserving its opening hour for elderly customers. On my most recent shopping trip, the store had instituted “one-way” aisles to ensure physical distancing and all customers were required to wear face coverings.

Some of these measures were mandated; some were voluntary. All track what the store’s customers, employees, and community would expect a responsible grocery store to do under the circumstances based on available information.

Conversely, companies that act contrary to stakeholder expectations for responsible conduct, even if the actions are legal and contribute to the bottom line, risk losing the trust of customers, investors, and regulators. Large public corporations that secured millions of dollars of loans under the Paycheck Protection Program intended for small businesses, for example, have endured substantial public criticism prompting some companies to return the funds. The angry reaction should not have been a surprise for corporate leaders paying attention to stakeholder expectations.

Philanthropy is not a substitute for responsibility.

Stakeholders expect responsible companies with the resources to do so, to give money and to tap their expertise during a crisis. Many businesses, large and small, have responded to the pandemic by providing financial or in-kind support to healthcare workers, to small businesses, and to international and community organizations addressing the impacts of COVID-19 on vulnerable populations.

Source: covid19responsefund.org/

Google has pledged more than $800 million to support small businesses, health organizations and governments, and health workers on the frontline of the global pandemic. The company’s contribution includes $250 million in advertising credits to help the World Health Organization and more than 100 government agencies disseminate information on how to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Citigroup is donating a total of $15 million to the United Nations Foundation and World Health Organization’s COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund, to No Kid Hungry to support emergency food-distribution programs in the United States, and to international efforts in countries that are severely affected by the pandemic. The British and Dutch consumer goods multinational Unilever is contributing €100 million through donations of soap, sanitizer, bleach and food, including adapting its manufacturing lines to produce sanitizer for use in hospitals.

All of these efforts are welcome.

Philanthropy, however, does not excuse a company from acting responsibly elsewhere in its operations.

Source: www.ethicalconsumer.org

Amazon faces intense criticism for failing to adequately protect its employees from the outset of the pandemic; resisting paid sick time, hazard pay, and health benefits for part-time employees; and retaliating against a warehouse worker who protested working conditions. Since then, Amazon has enhanced its health and safety practices, hired 175,000 additional employees, and donated thousands of laptops to Seattle public school students, among other efforts. CEO and Founder Jeff Bezos announced a $100 million gift to Feeding America. The company’s philanthropic responses alone, however, are proving insufficient to meet stakeholder expectations for responsible conduct. Employees continue to protest Amazon’s working conditions and policies, and regulators have launched investigations into the company’s labor practices.

McDonald’s Corporation has donated over $3 million in food to support local communities during the COVID-19 pandemic; yet, more than half a million McDonald’s workers without access to paid sick leave are serving food nationwide.

Leading companies act and give responsibly.

Business leaders are called to act when government fails to do so.

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a crisis of government capacity and leadership. Corporate responsibility today means filling these governance gaps.

Business leaders should be prepared to address the governmental pandemic response by speaking out against harmful policies and advocating for responsible solutions.

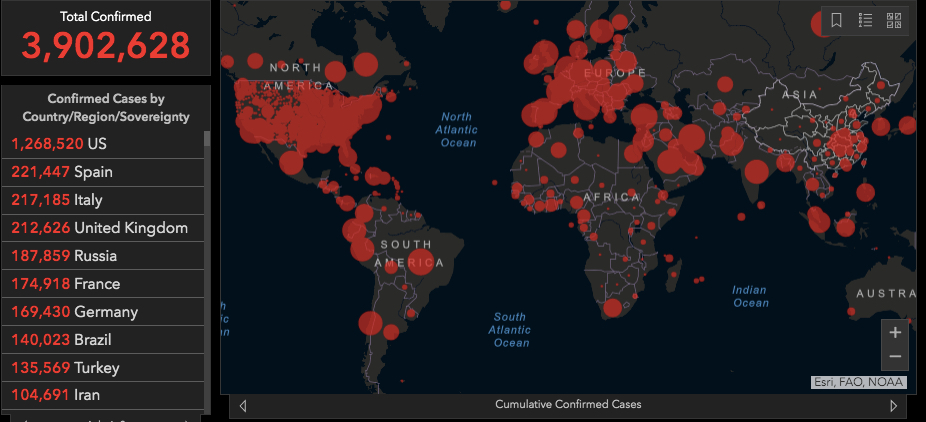

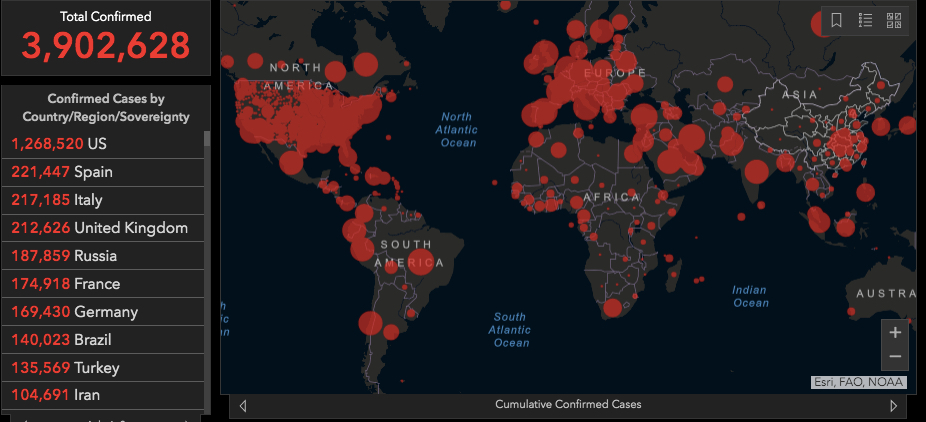

Source: coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html, visited 5/8/2020

Responsible companies in the United States are meeting public needs that the federal government has failed to address. Companies in many different sectors are stepping in to manufacture, purchase, and distribute personal protective equipment; to accelerate production of diagnostic tests and medical equipment like ventilators; and to disseminate accurate data on the virus and its spread. Microsoft voluntarily told its employees to work from home in support of local health authorities’ efforts to communicate the urgency of the looming pandemic in Seattle. Apple and Google are partnering to develop contact tracing technology to help governments and health agencies reduce the spread of the virus.

Stakeholders increasingly expect corporate leaders to speak out on public policy issues, [3] such as gun violence and immigration policy, [4] when government fails to act or causes harm. COVID-19 is accelerating this trend. In his annual letter to CEOs, Larry Fink, the chairman and CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, noted last year that “stakeholders are pushing companies to wade into sensitive social and political issues — especially as they see governments failing to do so effectively.” Fink called on CEOs to demonstrate leadership and corporate commitment to “to the countries, regions, and communities where they operate, particularly on issues central to the world’s future prosperity.” No issue meets these criteria right now more than the multi-dimensional COVID-19 crisis.

CEOs that understand and anticipate the potential impacts on of all of their company’s stakeholders are not rushing to reopen.

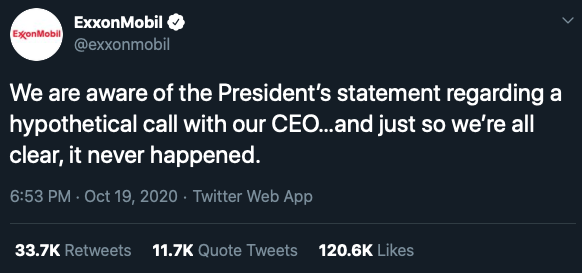

Business leaders should be prepared to address the governmental pandemic response by speaking out against harmful policies and advocating for responsible solutions. Consumer product brands have had to correct inaccurate information about disinfectants. Many businesses in the United States must now decide whether to reopen against data-driven public health guidance. CEOs that understand and anticipate the potential impacts on of all of their company’s stakeholders are not rushing to reopen.

Unprecedented in its scope, the COVID-19 pandemic presents a unique opportunity for companies and their leaders to live their values by acting responsibly.

Logos Senior Advisor Anthony Ewing counsels executives on corporate responsibility and works with clients to establish and strengthen crisis management programs. He teaches a graduate seminar on corporate responsibility at Columbia Law School.

Notes

[1] Helio Fred Garcia, “Leadership, Communication, and COVID-19,” (Mar. 25, 2020) https://logosconsulting.net/leadership-communication-and-covid-19/.

[2] Anthony Ewing, “Integrating Human Rights into Crisis Planning,” A Good Practice Note endorsed by the United Nations Global Compact Human Rights and Labour Working Group (6 October 2015), https://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/issues_doc/human_rights/Human_Rights_Working_Group/crisis-planning-GPN.pdf.

[3] Aaron K. Chatterji and Michael W. Toffel, “The New CEO Activists,” Harvard Business Review (January–February 2018), https://hbr.org/2018/01/the-new-ceo-activists.

[4] Anthony Ewing, “Business and Human Rights: Lessons for Managing the Trump Presidency,” blog post, February 13, 2017, https://logosconsulting.net/business-and-human-rights-lessons-for-managing-the-trump-presidency/.

Maida is an Advisor at Logos Consulting Group and a Senior Fellow at the Logos Institute for Crisis Management and Executive Leadership, where she helps corporate leaders maximize presence and enhance communication skills to become more effective in managing both their reputations and relationships. She also serves as the Chief of Client Services.

Maida is an Advisor at Logos Consulting Group and a Senior Fellow at the Logos Institute for Crisis Management and Executive Leadership, where she helps corporate leaders maximize presence and enhance communication skills to become more effective in managing both their reputations and relationships. She also serves as the Chief of Client Services. Leaders change the world. But they don’t do it alone. They ignite others toward a common cause. At Logos Consulting Group, we believe in this world and we see this world in the work that we do. Our mission is to build a better world by equipping people to become leaders who ignite change in the world for the good. We do this by helping our clients inspire those who matter to them to make a difference in their own industries and communities, and the world at large. We advise and coach our clients in three key areas:

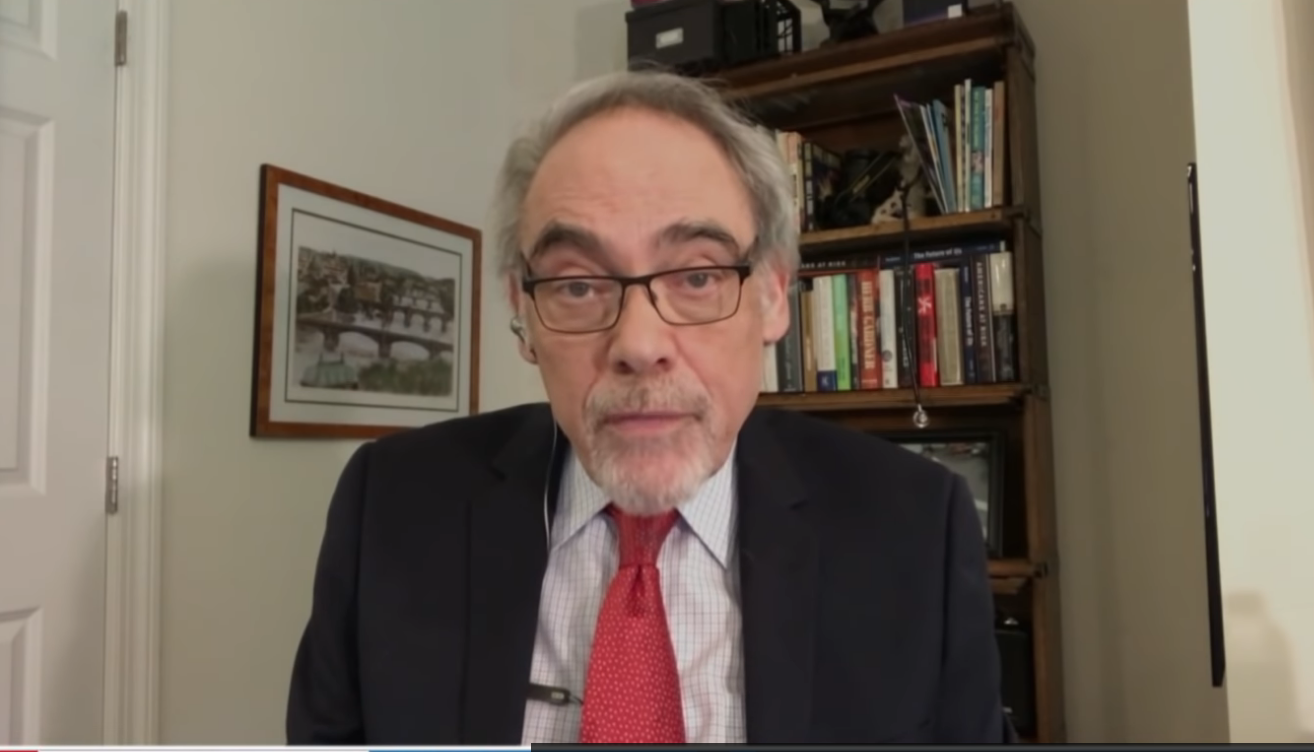

Leaders change the world. But they don’t do it alone. They ignite others toward a common cause. At Logos Consulting Group, we believe in this world and we see this world in the work that we do. Our mission is to build a better world by equipping people to become leaders who ignite change in the world for the good. We do this by helping our clients inspire those who matter to them to make a difference in their own industries and communities, and the world at large. We advise and coach our clients in three key areas:  On November 9, 2020, Helio Fred Garcia spoke with Will Bachman on his podcast

On November 9, 2020, Helio Fred Garcia spoke with Will Bachman on his podcast

Companies without a pandemic crisis plan in place can still identify potential impacts to guide their response. Enterprise-wide impact mapping and assessment can help an organization prioritize next steps. By

Companies without a pandemic crisis plan in place can still identify potential impacts to guide their response. Enterprise-wide impact mapping and assessment can help an organization prioritize next steps. By  Similarly, companies that

Similarly, companies that  On my first trip to the grocery store after a statewide “stay-at-home” order had been issued, the store had placed limits on the number of scarce items that customers could buy, like cleaning products and milk. Employees were working hard to keep shelves stocked. Two weeks later, consistent with evolving public health guidance, the store was limiting the number of customers allowed inside at once, plexiglass shields had been placed between checkout workers and customer payment stations, and all store employees wore gloves and masks. The grocery chain had also adopted an industry-wide practice reserving its opening hour for elderly customers. On my most recent shopping trip, the store had instituted “one-way” aisles to ensure physical distancing and all customers were required to wear face coverings.

On my first trip to the grocery store after a statewide “stay-at-home” order had been issued, the store had placed limits on the number of scarce items that customers could buy, like cleaning products and milk. Employees were working hard to keep shelves stocked. Two weeks later, consistent with evolving public health guidance, the store was limiting the number of customers allowed inside at once, plexiglass shields had been placed between checkout workers and customer payment stations, and all store employees wore gloves and masks. The grocery chain had also adopted an industry-wide practice reserving its opening hour for elderly customers. On my most recent shopping trip, the store had instituted “one-way” aisles to ensure physical distancing and all customers were required to wear face coverings.

Helio Fred Garcia, known as the Global Crisis Advisor, has helped leaders build trust, inspire loyalty, and lead effectively for more than 40 years. He is a coach, counselor, teacher, writer, and speaker whose clients have included more than 400 CEOs of some of the largest and best-known companies and organizations in the world, in dozens of countries on six continents.

Helio Fred Garcia, known as the Global Crisis Advisor, has helped leaders build trust, inspire loyalty, and lead effectively for more than 40 years. He is a coach, counselor, teacher, writer, and speaker whose clients have included more than 400 CEOs of some of the largest and best-known companies and organizations in the world, in dozens of countries on six continents.