|

Kristin Johnson | Bio | Posts

7 Oct 2014 | 5:25PM |

A contagious disease – first presenting in several West African countries – is now a pandemic, crossing continents and striking virulent fear in the U.S., Spain and around the world.

- The virus incubates.

- Victims often do not realize they are infected.

- Millions around the world – including those right here in the U.S. – are afflicted.

- There can be deadly consequences.

- I am not referring to Ebola.

Diagnosis

The malady I speak of is miscommunication, with side effects including misinformation, confusion and fear that drive outcomes at every level of community response.

Communication – or lack of – is what is arguably at the center of disease control and care. Ebola is no exception. While Ebola is infectious – meaning that it is likely to spread upon exposure – the actual transmission, or contagiousness of the disease, is reportedly low given transmission is from contact with an infected person’s bodily fluids.

Miscommunication, however, is highly contagious and on the rise.

The Spread of Miscommunication

Today, news emerged that a Spanish nurse tested positive for Ebola after minimal exposure. According to a report on NPR quoting Dr. Antonio Alemany, a health official from the regional government of Madrid, the nurse “entered the infected priest’s room twice – once to treat him and once after he died to collect some of his things” and as far as health official know, the nurse “was wearing a protective suit the whole time and didn’t have any accidental contact with him.”

Miscommunication changes everything about what we thought we understood about the spread of the deadly disease, Ebola, and risk management. Fears are now elevated among healthcare workers, governments, media and people around the world because doubt has been cast on what we thought we knew about transmission. If the nurse, suited in protective gear, gets sick after minimal contact with an infected patient, what does that mean for the rest of us? There is no central, trusted authority on this issue to address this question or the many others being raised in the 24-hour news cycle world. The U.S. Centers for Disease and Control (CDC) hasn’t updated the “latest news” portion of its website in more than 48 hours.

Instead, media outlets – competing with each other for viewers and readers – are spitting out puzzle pieces of a larger story in a rush to be the ‘breaking news’ source, which is spreading alarm worldwide. Uncertainly is leading to panic and, in the absence of a clear solution, a public outcry to simply do something – without a clear assessment of actions and outcomes.

Symptoms Rising

The pressure to do something is mounting. Just this morning, there were calls for the resignation of Spain’s health minister, Ana Mato, in response to the “safety lapse” after the nurse’s infection. In the U.S., there are cries to shut down U.S. borders to anyone who has been to West Africa and the White House, which objects to blocking flights from West Africa, is in discussion to appoint CDC staffers to certain airports to screen passengers. Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy today declared Ebola a public health emergency, signing an order for state health officials to quarantine individuals or groups “exposed to the virus or, worst case, infected.”

According to Sarah Crowe, UNICEF’s chief of crisis communications, in an interview with Columbia Journalism Review online, “It’s all so new that you can’t say that any one organization had figured out protocols. It’s unmapped terrain, whether you’re at it from child protection to precautions for the media.”

While the disease – which brings the prospect of isolation and death – is terrifying, the confusion over risk, containment and care is what truly is driving fear and potentially dangerous, impulse responses. It’s fight or flight, challenging humans’ most basic needs to preserve physiological wellness and safety (Maslow).

While there may be authorities that do fully understand Ebola – including risk, containment and care – it takes coordination on the part of governments, health care institutions, care providers, media and communities to manage the communication. This includes the ability to impart urgency for resources, discipline in safety protocols and transmission risk to vulnerable populations. It is also of paramount to get the right message to the right audience at the right time. But that is where we, as a world, are struggling.

Some public health specialists now speculate an asymptomatic person infected with Ebola could spread the virus to others. Dr. Philip K. Russell, a virologist who, according to LA Times online, “oversaw Ebola research while heading the U.S. Army’s Medical Research and Development Command, and who later led the government’s massive stockpiling of smallpox vaccine after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks” acknowledged that we are working with an unknown. According to Dr. Russell, “scientifically, we’re in the middle of the first experiment of multiple, serial passages of Ebola virus in man….God knows what this virus is going to look like. I don’t.”

In Search of a Cure

While statements such as Dr. Russell’s discourage hope of clarity any time soon on the disease management of Ebola, what we do have is a strategy to combat miscommunication: ordered thinking.

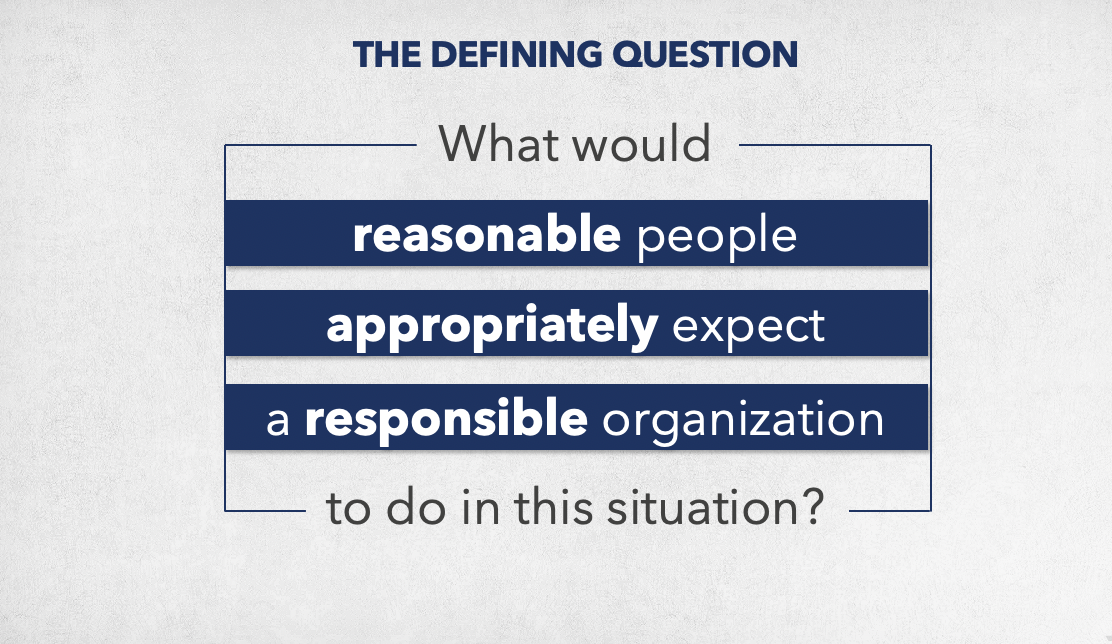

Pulling from The Power of Communication, by Helio Fred Garcia, it is important to never confuse means with ends or goals and strategies with tactics. In order to at the very least provide some guidance to a world that is impulsively responding to the terror of uncertainty, a unity of effort on three levels can help foster clarity:

(From The Power of Communication, Chapter 6)

- Strategy: The strategic level is focused directly on the objective, beginning with the desired outcomes. Define the audience(s) and ask “what do we need people to think, feel, know and do” in order to achieve the goal?

- Operations: The operational level is focused on anticipating and adapting to the audience(s). The best manner, time, message and messenger should all be considered in this to better address concerns, fears and trust.

- Tactics: The tactical level is where communication with the audience(s) takes place.

George Bernard Shaw said, “The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” The miscommunication pandemic we are dealing with is greater than Ebola. Why?

Ebola alone is not a global health problem; it is a global health problem because its contagion, containment and care protocols are unclear.

As a result of this uncertainty – a communication problem on many levels – the infections and fear are multiplying.

Among the inconsistency, speculation and chaos surrounding Ebola, the world needs a trusted authority to emerge with calm guidance and a clear message to help address the fear. But among all the uncertainty, it seems only more questions develop.

Today I ask, who will this authority be and, in the absence of a cure, what messages will this person deliver? Do you agree that a communication issue is at the center of this pandemic? Feedback welcome.