A version of this post appeared in CommPro.biz.

Last week Cornell University’s Alliance for Science published the first comprehensive study of coronavirus misinformation in the media, and concluded that President Trump is likely the largest driver of the such misinformation.

Lost in the News Cycle

In any other administration this would have led the news for at least a week.

But the report came five days after President Donald J. Trump nominated Amy Coney Barrett to the U.S. Supreme Court. It came four days after publication of a massive New York Times investigation that revealed that President Trump paid no federal income taxes for years. It came just two days after the debate debacle in which the President refused to condemn white supremacy and seemed to endorse the Proud Boys. And it came just hours before the news that the President and First Lady had tested positive for COVID-19.

I wish the President and the First Lady a speedy and complete recovery.

But it is important that this news not be lost, and that the President be held accountable for the consequences of his words, actions, and inaction.

Language, Inaction, and Consequences

I am a professor of ethics, leadership, and communication at Columbia University and New York University. This summer my book about Trump’s language and how it inspires violence was published. I finished writing Words on Fire: The Power of Incendiary Language and How to Confront It in February. But since then the effect of Trump’s language has been even more dangerous.

In the book, I document how charismatic leaders use language in ways that set a powerful context that determines what makes sense to their followers. Such leaders can make their followers believe absurdities, which then can make atrocities possible. If COVID-19 is a hoax, if it will magically disappear, if it affects only the elderly with heart problems, then it makes sense for people to gather in large crowds without social distancing or masks.

There’s just one problem. None of that is true. But Trump said all those things. And his followers believed him. And the President and his political allies refused to implement policies to protect their citizens.

What The President Knew, and When The President Knew It

As I write this, 210,000 Americans have died of COVID-19 and the President is being treated for it at Walter Reed Military Medical Center.

But it didn’t have to happen. Three weeks ago Dr. Irwin Redlener, head of Columbia University’s Pandemic Resource and Response Initiative, estimated that if the nation had gone to national masking and lock-down one week earlier in March, and had maintained a constant masking and social distancing policy, 150,000 of fatalities could have been avoided.

Trump knew about the severity of the virus in February and March.

In taped discussions Trump told Washington Post Associate Editor Bob Woodward what he knew about how dangerous COVID-19 is:

- It is spread in the air

- You catch it by breathing it

- Young people can get it

- It is far deadlier than the flu

- It’s easily transmissible

- If you’re the wrong person and it gets you, your life is pretty much over. It rips you apart

- It moves rapidly and viciously.

- It is a plague

But he was telling the nation the opposite.

“Infodemic” of COVID-19

The Report Cover

President Trump likes to label anything he doesn’t agree with Fake News. But it turns out that he’s the largest disseminator of misinformation about Coronavirus.

Cornell University’s Alliance for Science analyzed 38 million pieces of content published in English worldwide between January 1 and May 26, 2020. It identified 1.1 million news articles that “disseminated, amplified or reported on misinformation related to the pandemic.”

On October 1, 2020 the Alliance published its report. It notes,

“These findings are of significant concern because if people are misled by unscientific and unsubstantiated claims about the disease, they may attempt harmful cures or be less likely to observe official guidance and thus risk spreading the virus.”

Its conclusion:

“One major finding is that media mentions of President Trump within the context of different misinformation topics made up 37% of the overall ‘misinformation conversation,’ much more than any other single topic.

The study concludes that Donald Trump was likely the largest driver of the COVID-19 misinformation ‘infodemic.’

In contrast only 16% of media mentions of misinformation were explicitly ‘fact-checking’ in nature, suggesting that a substantial quantity of misinformation reaches media consumers without being challenged or accompanied by factually accurate information.”

But Trump may be responsible for more than the 37% of the news stories that name him. The report says that

” a substantial proportion of other topics was also driven by the president’s comments [but did not explicitly name him], so some overlap can be expected.

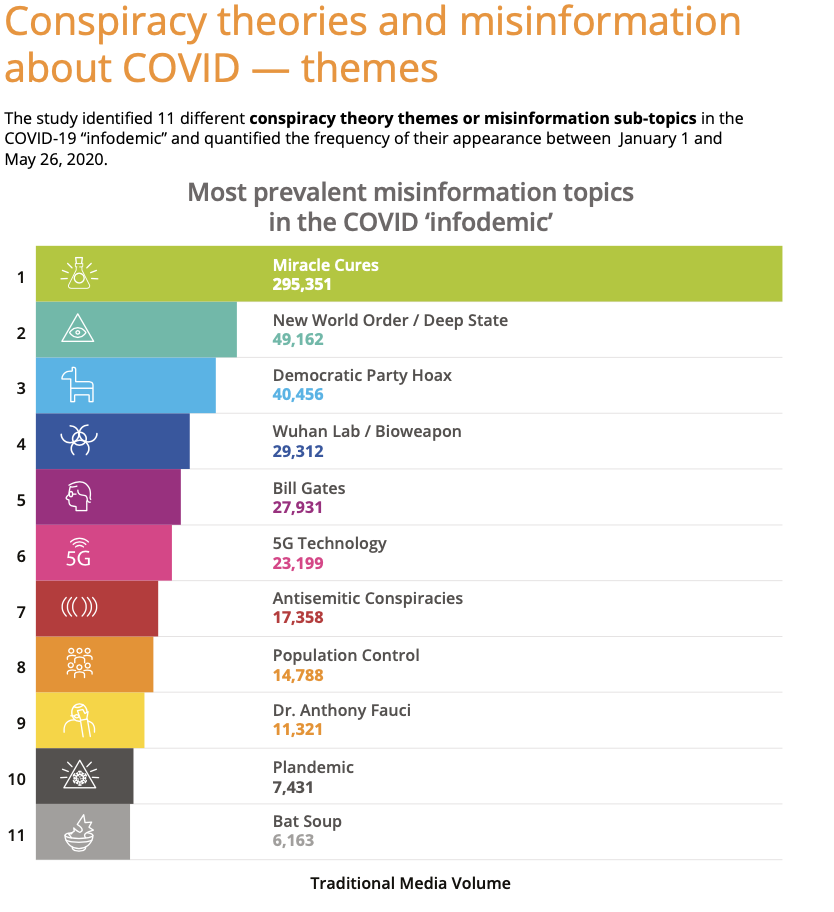

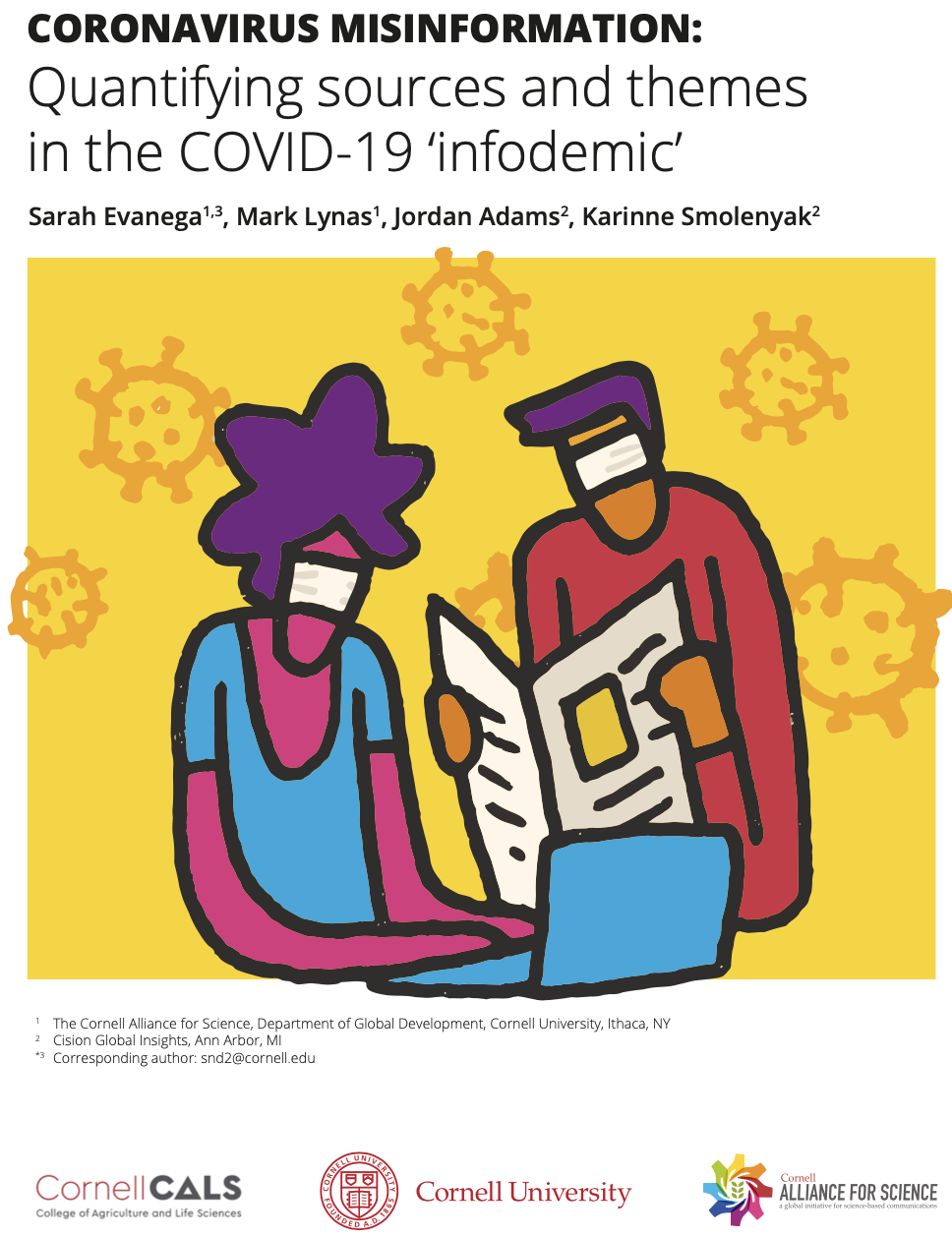

Graphic from Cornell Alliance for Science Report

The most prevalent misinformation was about miracle cures. More than 295,000 stories mentioned some version of a miracle cure. (Note that the study looked only at stories that were published before the end of May, long before the president’s statements about a vaccine being ready by the end of October.)

The report notes that Trump prompted a surge of miracle cure stories when he spoke of using disinfectants internally and advocated taking hydroxychloroquine.

The second most prevalent topic, mentioned in nearly 50,000 stories, was that COVID had something to do with the “deep state.” The report notes,

“Mentions of conspiracies linked to alleged secret “new world orders” or ‘deep state’ government bodies existed throughout the time period and were referenced in passing in conversations that mentioned or listed widespread conspiracies. Indeed, President Trump joked about the US State Department being a ‘Deep State’ Department during a White House COVID press conference in March.”

The third most prevalent misinformation was about COVID-19 being a Democratic hoax, mentioned in more than 40,000 stories.

Human Consequences of Misinformation

The report closes with a warning: Misinformation has consequences:

“It is especially notable that while misinformation and conspiracy theories promulgated by ostensibly grassroots sources… do appear in our analysis in several of the topics, they contributed far less to the overall volume of misinformation than more powerful actors, in particular the US President.

In previous pandemics, such as the HIV/AIDS outbreak, misinformation and its effect on policy was estimated to have led to an additional 300,000 deaths in South Africa alone.

If similar or worse outcomes are to be avoided in the present COVID-19 pandemic, greater efforts will need to be made to combat the “infodemic” that is already substantially polluting the wider media discourse.”

In my book, I help engaged citizens, civic leaders, and public officials recognize dangerous language and then confront those who use it. I urge such citizens and leaders to hold those who use such language responsible for the consequences.

I wish President Trump a full and fast recovery. He and those closest to him have now been affected by their own denial of science. I hope that now he can start to model appropriate safe behavior.

But even as Trump is being treated in the hospital his campaign says it will stay the course, including an in-person rally for Vice President Mike Pence the day after the vice-presidential debate in several days. This is both irresponsible and dangerous.

I urge civic leaders, engaged citizens, and public officials, regardless of party, to stop having super-spreader events such as in-person rallies. And finally to begin modeling responsible behavior: Wear a mask, maintain social distancing. Masking and distancing are not political acts; they are a civic responsibility.

On November 9, 2020, Helio Fred Garcia spoke with Will Bachman on his podcast

On November 9, 2020, Helio Fred Garcia spoke with Will Bachman on his podcast