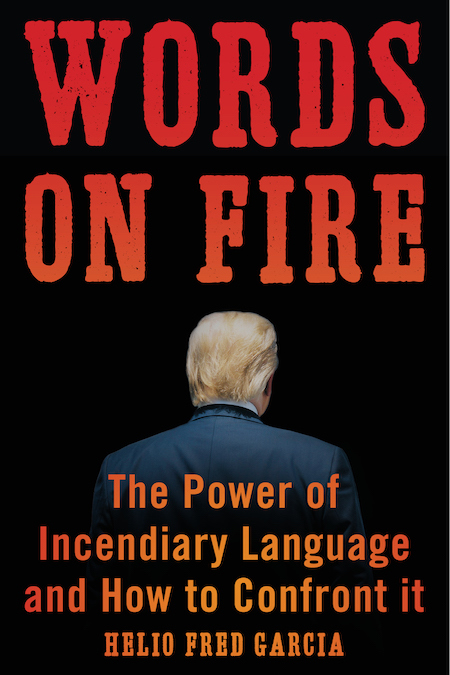

Logos Consulting Group is pleased to announce that the next book by Logos President Helio Fred Garcia is now available for pre-order.

Words on Fire: The Power of Incendiary Language and How to Confront It is about the power of communication to do great harm, and how civic leaders and engaged citizens can hold leaders accountable to prevent such harm. Garcia focuses on the forms of communication that condition an audience to accept, condone, and commit violence against a targeted group, rival, or critic.

Sending Up a Flare

In the book’s preface Garcia writes,

“In my teaching and research, I study patterns: patterns that help leaders enhance competitive advantage, build trust and loyalty, and change the world for the better. I study the patterns of audience engagement and audience reaction. I study persuasion and influence, and the power of language to change people, mostly for the better.”

But he also provides a caution:

“I’ve also been acutely aware of the use of communication to hurt, to harm, and to humiliate, and of how dehumanizing and demonizing language can lead some people to commit acts of violence. I typically don’t teach those things in a classroom, but I often send up a flare, warning students, former students, and others of the predictable, if unintended, consequences of speech that, under the right conditions, can influence people to accept, condone and commit violence against members of a group.”

Garcia notes that he found himself sending up many flares in recent years, but that something changed in 2018. In the Fall of that year he posted on social media persistent warnings about stochastic terrorism, the technical term for language that provokes some people to commit violence. He says,

“My concern grew into alarm as the 2018 mid-term elections approached and as President Trump’s language crossed a line. I worried that someone would be killed by Trump followers who embraced his increasingly incendiary rhetoric about immigrants, Mexicans, Muslims, and critics.”

Garcia’s fears were soon realized.

“In a single week, about ten days before the mid-terms, two separate terror attacks took place: one killed eleven people at worship in a synagogue; one failed but had targeted a dozen Trump critics with mail bombs. In both cases the perpetrators justified their actions by quoting Trump language. One of them, the mail bomber, described his conversion from being apolitical to being ‘a soldier in the war between right and left’ that resulted from his several years in Trump’s orbit.”

The following day Garcia posted a blog on Daily Kos describing the relationship between language and violence. That post was republished by CommPro.biz. Words on Fire is the continuation of that original blog post.

In reflecting on the President’s language, Garcia noticed another pattern: the forms of his language were familiar. He realized that the president was using the very same rhetorical techniques that had preceded previous mass murders, including genocides. He worried that, left unchecked, the president would continue, with increasingly dire consequences.

Garcia explored the kinds of language that historically had preceded acts of mass violence. And he studied contemporary sources including the U.S. Holocaust Museum Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide. The center defines “dangerous speech” as:

“speech that increases the risk for violence targeting certain people because of their membership in a group, such as an ethnic, religious, or racial group. It includes both speech that qualifies as incitement and speech that makes incitement possible by conditioning its audience to accept, condone, and commit violence against people who belong to a targeted group.”

One of the key elements of creating such conditions is to dehumanize others. The Center’s handbook Defusing Hate notes that:

“Dangerous speech often dehumanizes the group it targets (e.g., by calling its members rats, dogs, or lice), accuses the target group of planning to harm the audience, and presents the target group’s existence as a dire threat to the audience.”

Garcia also studied the work of Yale University philosopher Jason Stanley, who says that when leaders persistently dehumanize others they lessen the capacity of citizens to empathize.

The Playbook

Dangerous speech begins with dehumanization but doesn’t end there. Garcia has identified twelve communication techniques that individually and collectively create a social context that conditions an audience to accept, condone, and commit violence against people who belong to a targeted group. Each technique is a bit different from the other, although the individual techniques have elements in common. They serve as a kind of Playbook that malicious leaders have used to divide communities and to accumulate power. The twelve forms are:

- Dehumanize: Calling groups of people animals or vermin who are infesting the nation.

- Demonize/Delegitimize: Attributing to a group or rival a menacing, evil identity or calling into question the legitimacy or qualification of a group or rival.

- Scapegoat: Blaming a group for all or many of the nation’s problems.

- Public Health Threat: Claiming that members of a group are carrying or transmitting dangerous diseases.

- Safety Threat: Claiming that a group, rival, or critic is a threat to public safety – likely to cause death or injury to the nation or to the dominant group – or is a threat to civic order.

- Violent Motive: Claiming that a group has violent or hostile intentions toward a dominant group.

- Severely Exaggerating Risk: Labelling a minor issue or routine event a major threat.

- Sinister Identities: Attributing vague or sinister identities to a group or its members.

- Conspiracy: Saying that something is part of a sinister conspiracy.

- Discredit Information: Discrediting the source of objective information or of information critical of the leader.

- Conflation: Conflating the leader and the state, so that any criticism of the leader is seen as an attack on the nation.

- Menacing Image: Juxtaposing a menacing image (noose, swastika, flaming cross) with a person or person’s image, a location, or a facility associated with the target.

Words on Fire documents these forms of communication, and the consequences of that language, both before Trump and by Trump.

But it does more. It assesses how American political life came to this dangerous and demoralizing place.

And it offers hope, a path forward: a framework, a mindset, and a set of techniques to help civic leaders and informed citizens recognize the patterns of dangerous speech early, intervene early, hold those who use such language accountable for the consequences, and ideally prevent such violence in the first place.

Garcia and a team of researchers spent 14 months working on the book. In addition to studying historic mass killings that followed the persistent use of dangerous speech, Garcia and his researchers watched hundreds of rallies, interviews, and public appearances by Donald Trump as candidate and president, and read thousands of his tweets. Garcia also examined hate crime violence statistics and trends. And he examined national security and law enforcement scholarship on lone wolf violence up to and including lone wolf terrorism. Garcia synthesizes the fruits of this research and describes how lone wolves develop a terrorist mindset and how they are activated to commit violence.

From Stochastic Terrorism to Lone-Wolf Whistle Terrorism

Since 9/11 the use of communication in ways that trigger lone wolves to commit acts of violence, up to and including terrorism, has been known as stochastic terrorism. The name comes from a principle in statistics and describes something that may be statistically predictable but not individually predictable.

But Garcia has concluded that the phrase stochastic terrorism is difficult to grasp, and even to say, and tends to limit discussion. He proposes a different way to describe the phenomenon, based on who is motivated to act on the communication – lone wolves – and what triggers them to so act – a kind of dog whistle that he calls a lone-wolf whistle.

He says:

“Acts of violence triggered by such language I call lone-wolf whistle violence. When such language triggers mass violence with a political, ideological, or similar motive I call it lone-wolf whistle terrorism.”

A Call to Action

Words on Fire also profiles leaders who stepped over the line and were called on it. All, in their own ways and in varying time frames, stopped what they were doing. As responsible leaders do.

Garcia also explores humility as an essential leadership attribute that makes empathy possible. It is empathy that allows leaders to see the damage their rhetoric may cause, and humility and empathy that lead them to stop.

The book closes by providing a framework for civic leaders, engaged citizens, journalists, and public officials to recognize when a leader may have crossed the line, and a way to understand the likely consequences of dangerous speech. Garcia takes the Lone-Wolf Whistle Terrorism Playbook and recasts it as a toolkit or checklist in the form of questions to ask that can help determine whether a leader’s rhetoric is likely to inspire lone wolves to take matters into their own hands.

Early Endorsers

Early reaction to Words on Fire by those who have read the manuscript has been quite positive, and the book has several early endorsers.

David Lapan, Colonel, USMC (ret), former Pentagon and Department of Homeland Security spokesman, says:

“Language is power, and powerful. It can uplift, or harm. Helio Fred Garcia is an astute student of language and communication. This book offers historic examples, keen insights and valuable advice on recognizing patterns of language that can harm or lead to violence.”

Evan Wolfson, Founder, Freedom to Marry, says:

“Drawing on history and his deep expertise in communications, Helio Fred Garcia documents how Trump’s barrage of hate, divisiveness, falsehoods, and triggering are even uglier and more dangerous than we thought, right out of the autocrat’s playbook. During the Nixon administration, John Dean blew the whistle on the ‘cancer growing on the presidency.’ Words on Fire provides a clear and alarming CAT-scan of the cancer growing from this presidency, and a highly readable guide to how we can call out and combat Trump’s toxic language and malignant agenda, pushing back against the corrosive forces that enable Trumpism and put our country in such peril.”

James E. Lukaszewski, America’s Crisis Guru®, says:

“Many of us were taught a lie as youngsters that sticks and stones can break our bones, but words will never hurt us. Fred courageously, graphically and powerfully illustrates that it is words on fire that bloodlessly, without scars or visible traces cause deep internal permanent damage while often triggering accompanying physical damage. And that if we remain silent one victim incinerated by words on fire damages the rest of us.”

Lukaszewski adds,

“Words On Fire should be mandatory reading and a guide book for every reporter and editor anywhere. Journalists have significant responsibility for spreading the flames of intentionally incendiary, punitive, abusive language. There should be ethical and cultural sanctions for mindlessly but intentionally originating or transmitting dangerous language. Every business school needs to develop courses for managers and leaders in detoxifying and extinguishing fiery, intentionally emotional and harmful language, whatever the source, followed by every religious leader and elected official. Important institutions in our society and culture have the affirmative responsibility to stand up and speak out against the users and use of words on fire.“

Public reaction has also been positive. In the week after Words on Fire became available for Amazon pre-order, it became the Amazon #1 New Release in Rhetoric and #2 in New Releases in Public Administration the #3 best seller in Public Administration.

Words on Fire is scheduled for publication in mid-June. It is available for pre-order in both paperback and kindle edition.

Prior Books by Logos President

Words on Fire is Garcia’s fifth book. His first, published in 1998, was the two-volume Crisis Communications, now out of print.

In 2006 Garcia co-authored with his NYU colleague John Doorley Reputation Management: The Key to Successful Public Relations and Corporate Communication. That book’s fourth edition is scheduled for publication in late Spring. Reputation Management has been adopted in undergraduate and graduate public relations and communication programs around the world, and was published in Korean in Seoul in 2016,

In 2012 Garcia published The Power of Communication: Skills to Build Trust, Inspire Loyalty, and Lead Effectively. The Power of Communication has been adopted by dozens of graduate and professional schools, and was named one of eight leadership books on the U.S. Marine Corps Commandant’s Professional Reading List. It was published in Chinese in Beijing in 2014.

In 2017 Garcia published The Agony of Decision: Mental Readiness and Leadership in a Crisis. The Agony of Decision was named one of the best crisis management books of all time (#2 of 51) by BookAuthority, the leading non-fiction review site. It will be published in Chinese in Beijing later this year.

Garcia has been on the New York University faculty since 1988. He is an adjunct professor of management in NYU’s Stern School of Business Executive MBA program, where he teaches crisis management, and where he was named Executive MBA Great Professor. He is an adjunct associate professor of management and communication in NYU’s School of Professional Studies, MS in Public Relations and Corporate Communication program, where he twice received the Dean’s award for teaching excellence, in 1990 and in 2017. In that program he teaches courses in communication strategy; in communication ethics, law, and regulation; and in crisis communication.

Garcia is an adjunct associate professor of professional development and leadership at Columbia University, where he teaches ethics, crisis, and leadership in the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science. Garcia is also a Senior Fellow in the Institute of Corporate Communication at Communication University of China in Beijing.