The following is an excerpt of a guest column by Helio Fred Garcia published on August 10, 2022 by New York University School of Professional Studies’ biweekly LinkedIn newsletter, The Pitch.

Misinformation kills. Both people and democracy.

In May, the head of the Food and Drug Administration warned that misinformation has become the leading cause of death in the United States.

In 2020 misinformation about COVID-19 led to the worst handled pandemic response in the developed world and caused hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths. Starting in mid-2021 misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine and vaccinations continued the wave of preventable fatalities.

As of mid-summer 2022, more than one million Americans – one in every 324 – has died of COVID-19.

The risks of misinformation go well beyond public health. The January 6 Committee hearings show how misinformation inspired thousands of people to attack the Capitol on the day that the 2020 presidential election was to be certified. Some of those domestic terrorists sought out and threatened to assassinate Vice President Mike Pence, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and other members of Congress.

But misinformation doesn’t just put human life at risk. Misinformation risks killing democracy itself.

Political misinformation continues as hundreds of candidates for state office persist in trafficking in the Big Lie that the 2020 election was stolen, and promise to take control of the voting bureaucracy in many states. Misinformation also erodes civic trust and the public’s confidence in civic institutions, which are essential for democracy to work.

COVID-19 Misinformation

Cornell University’s Alliance for Science conducted the first comprehensive study of COVID-19 misinformation. It reviewed more than one million articles with COVID-19 misinformation published in the first six months of the pandemic. It found that President Donald Trump was directly quoted in 37 percent of all instances of misinformation. But when the researchers included Trump misinformation that was retold by others, they concluded that he was responsible for fully 50 percent of all misinformation statements about COVID.

The study concluded that Trump was “likely the largest driver of the COVID-19 misinformation ‘infodemic.’”

It further noted that:

“These findings are of significant concern because if people are misled by unscientific and unsubstantiated claims about the disease, they may attempt harmful cures or be less likely to observe official guidance and thus risk spreading the virus.”

We saw just this phenomenon play out in the summer of 2020.

In the final two months of Trump’s presidency, vaccines were approved and distributed to the individual states. But there was no plan on how to get the vaccines into people’s arms. Even worse, there was no public education campaign to help citizens understand the vaccine’s safety and efficacy, or to promote the civic duty to get vaccinated in order to stop the spread.

U.S. Army four-star general Gus Perna, who managed Operation Warp Speed (OWS), which developed and delivered vaccines in record time, notes that this failure gave an opening for misinformation to flourish:

“Where was the long-term strategy for getting people ready to start taking the vaccine? … That was not part of the OWS portfolio. It’s a personal choice to get the vaccine or not. But where was the presentation to inform everybody, so that they could make the best decision? Where was the responsibility to not let this get politicized? … It just didn’t exist.”

And in that information vacuum, vaccine skeptics, and later political actors opposed to President Joe Biden, spread vaccine misinformation that continues to the present day. More than a third of Americans are not fully vaccinated. A Kaiser Family Foundation analysis in April concluded that nearly a quarter million COVID-19 deaths between June 2021 and March 2022 could have been prevented with vaccinations:

“These vaccine-preventable deaths represent 60% of all adult COVID-19 deaths since June 2021, and a quarter (24%) of the nearly 1 million COVID-19 deaths since the pandemic began… Unvaccinated people now represent a small share of the population, but a majority of COVID-19 deaths.”

The Fraud About Election Fraud

The January 6 Committee hearings have definitively demonstrated that the Big Lie claiming that the 2020 election was stolen was not only false but known by President Trump and his inner circle to be false.

Then-Attorney General Bill Barr, who for 22 months had been sycophant-in-chief for Trump, eventually told truth to power. After the 2020 election Barr told Trump that the Department of Justice had investigated all the claims of voter fraud and concluded that there was none.

Barr testified to the committee:

“I made it clear I did not agree with the idea of saying the election was stolen and putting out this stuff, which I told the president was bullshit.”

After the January 6 attack failed to prevent the certification of electors, Trump was still repeating the lie that he had actually won the election. In out-takes of a video the day after the attack, presented by the January 6 Committee, Trump told his staff, “I don’t want to say the election is over.”

In early July 2022, more than 20 months after the 2020 election, Trump called the Wisconsin House Speaker and urged him to overturn Wisconsin’s 2022 election results. In its coverage of that phone call, NBC News noted that Trump “has repeatedly claimed without evidence” that there was widespread voter fraud.

In mid-July 2022, more than 18 months after the January 6 attack, Trump told a rally in Arizona, “I ran twice. I won twice and did much better the second time than I did the first, getting millions more votes in 2020 than we got in 2016.” While the second half of the sentence is true – he did get more popular votes in 2020 than in 2016 – the first part of the sentence, for which the second is support, is false. He did not win the presidency twice. In 2020 Joe Biden received more popular and electoral votes than Trump did. But much of the news media ran his quote without noting that it was false.

Communicators’ Professional Obligation to Combat Misinformation

Tim Snyder, Yale history professor and author of On Tyranny, wrote in the New York Times after the January 6 attack,

“Post-truth is pre-fascism… Without agreement about some basic facts, citizens cannot form the civil society that would allow them to defend themselves. If we lose the institutions that produce facts that are pertinent to us, then we tend to wallow in attractive abstractions and fictions. Truth defends itself particularly poorly when there is not very much of it around.”

Silence, in the face of misinformation, is complicity. Whether among civic leaders or communication professionals – in journalism, public relations, marketing, and public affairs.

The slogan on the Washington Post masthead is “Democracy Dies in Darkness.” It refers to the news media’s obligation to truth, especially when misinformation is putting democracy at risk.

Public relations professionals share a similar duty. The Public Relations Society of America’s Code of Ethics makes clear how those of us whose profession is influencing public opinion have a particular duty. The Code’s first principle is:

“Protecting and advancing the free flow of accurate and truthful information is essential to serving the public interest and contributing to informed decision making in a democratic society.”

Under the Code, the first three obligations of a public relations professional are:

“Preserve the integrity of the process of communication. Be honest and accurate in all communications. Act promptly to correct erroneous communications for which the practitioner is responsible.”

So what can professional communicators do?

We can recognize that misinformation is a significant problem and that communication professionals have a particular standing to take the problem seriously. And once we take the problem seriously, we can deploy our gifts to tackle the problem head on:

- First, don’t be a misinformation mercenary. Don’t create or disseminate misinformation, on your own or for a client. Just say No when invited to help others lie.

- Second, call out the misinformation when you see it. Diminish the likelihood that it will take hold and become the new normal. Our obligation as professional communicators extends well beyond not lying. It includes preserving the integrity of the communication process. Communication professionals are far more likely to recognize intentionally misleading information early than the public at large is. As important, we have the capacity and tools to call attention to it.

- Third, rally other communicators – journalists, PR people, marketers, public affairs leaders – to do the same.

Just one example: In late July public relations wise man and executive editor of Business in Society John Paluszek wrote a LinkedIn column in which he called misinformation a “pandemic of the mind.” He provided tools and links to help communicators and others become well informed about misinformation and its antidotes.

Paluszek called on journalists and PR pros to work to confront the pandemic. At the strategic level, he says, it requires prioritizing the issue; committing for the long term; and persisting. And at the tactical level, Paluszek advises, “communicate, communicate, communicate.”

I am doing that now, in this column; and you can as well. Engage your network, as we professional communicators know how to do, and turn our individual efforts into a movement.

One way to think about American democracy and misinformation is the proverbial frog in a pot of water on a stove. American democracy is the frog. The information environment is the water. Misinformation is the flame that heats the water. And many Americans may not notice the water getting warmer. It’s our job to sound the alarm, and to remove the water from the source of heat – before it is too late.

The power of communication has never been stronger. The risks of misinformation have never been more serious. And the need for communicators to protect the integrity of the communication process – and thereby to protect democracy – has never been greater.

Read the full guest column and more from The Pitch here.

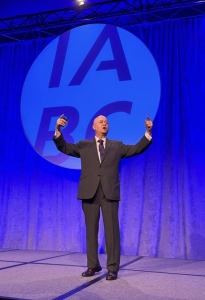

Garcia examined the ways in which disinformation and misinformation can – and have – put human life and democracy at risk. He then outlined a disinformation playbook that, once known, can be used to stop the spread of disinformation.

Garcia examined the ways in which disinformation and misinformation can – and have – put human life and democracy at risk. He then outlined a disinformation playbook that, once known, can be used to stop the spread of disinformation. The John W. Hill Award, PRSA-NY’s highest honor, recognizes professional achievement in the practice of public relations. Named for the founder of one of the world’s preeminent PR firms, the award has been presented annually since 1977. Previous recipients have included Jon Iwata, Fellow of Yale School of Management, Andy Polansky, CEO of Weber Shandwick, and James E. Lukaszewski, America’s Crisis Guru® and a mentor of Garcia.

The John W. Hill Award, PRSA-NY’s highest honor, recognizes professional achievement in the practice of public relations. Named for the founder of one of the world’s preeminent PR firms, the award has been presented annually since 1977. Previous recipients have included Jon Iwata, Fellow of Yale School of Management, Andy Polansky, CEO of Weber Shandwick, and James E. Lukaszewski, America’s Crisis Guru® and a mentor of Garcia. For 40 years, Garcia has helped leaders build trust, inspire loyalty, and lead effectively. He is a coach, counselor, teacher, writer, and speaker whose clients include some of the largest and best-known companies and organizations in the world. He is the author of five books on crisis, communication, and leadership. Garcia is an adjunct professor at the NYU Stern School of Business and an adjunct associate professor of management and communication in NYU’s School of Professional Studies,

For 40 years, Garcia has helped leaders build trust, inspire loyalty, and lead effectively. He is a coach, counselor, teacher, writer, and speaker whose clients include some of the largest and best-known companies and organizations in the world. He is the author of five books on crisis, communication, and leadership. Garcia is an adjunct professor at the NYU Stern School of Business and an adjunct associate professor of management and communication in NYU’s School of Professional Studies,