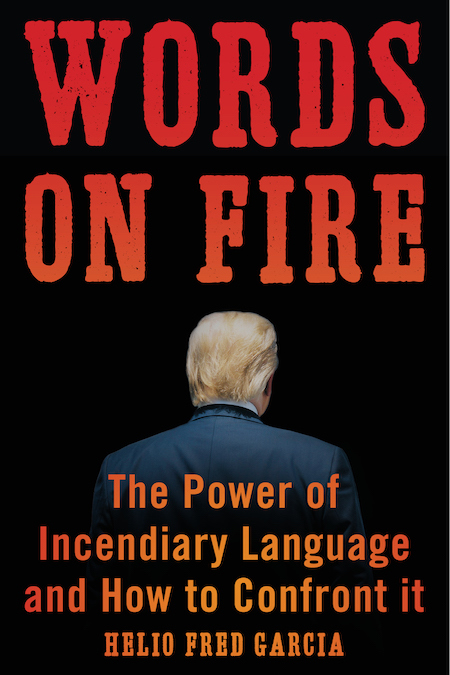

This guest column by Helio Fred Garcia was released on CommPro.biz on November 2, 2020.

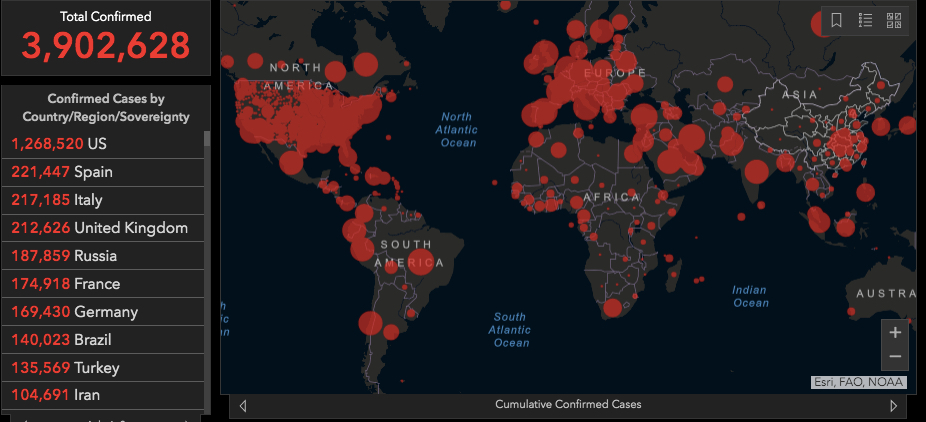

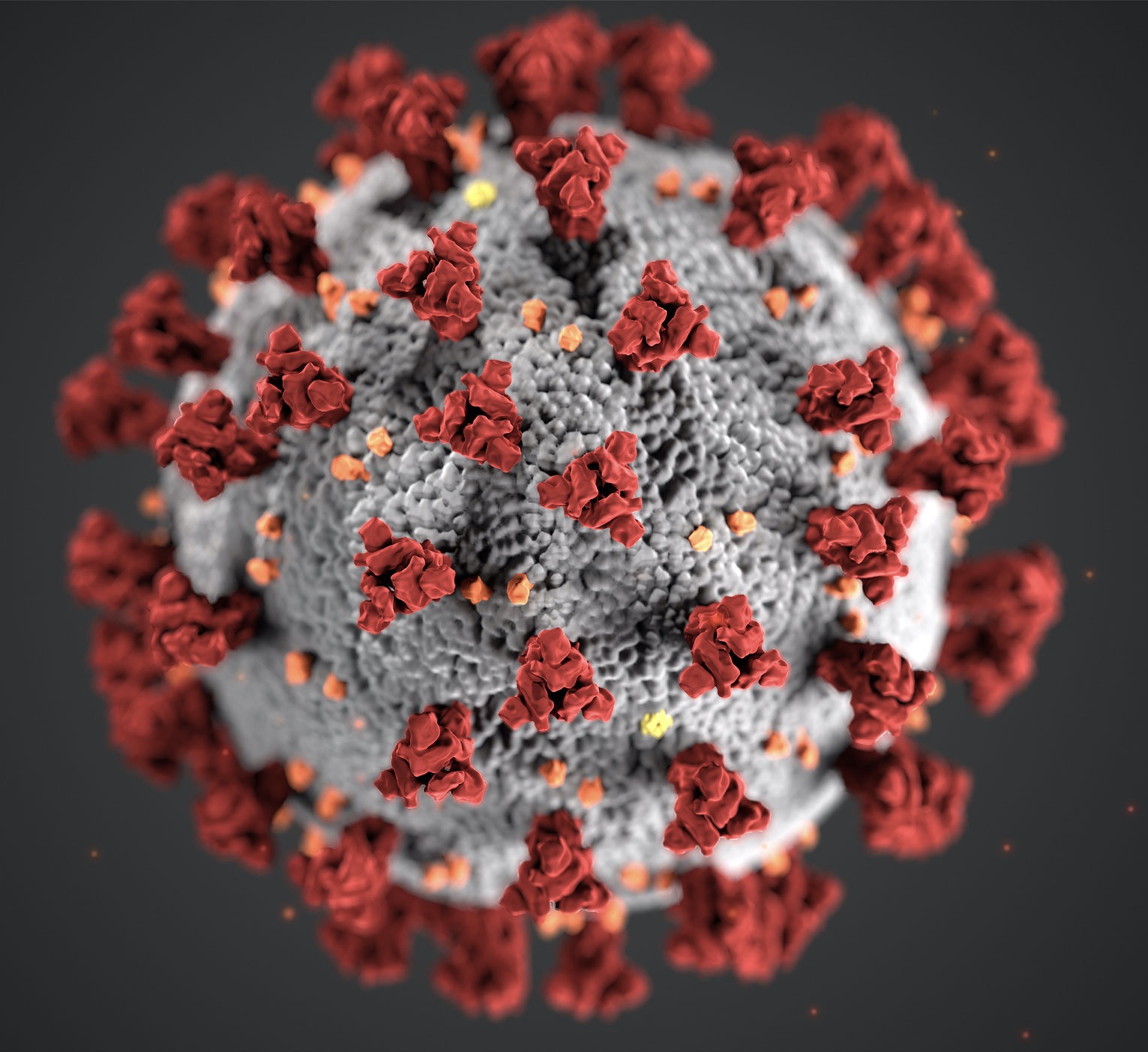

Here’s where the United States stands on the eve of the election: We have more than 9 million confirmed COVID-19 infections. We’re at nearly 100 thousand new cases daily; more than a thousand daily fatalities. We’re well on our way to be at a quarter million fatalities in a matter of weeks; half a million by the inauguration.

I have previously called the nation’s COVID-19 response the single-worst handled crisis, and the single largest leadership failure, in the nation’s history. Over the weekend, Dr. Anthony Fauci told The Washington Post that the nation needs to make an “abrupt change” and that we’re “in for a whole lot of hurt.”

If Donald Trump is re-elected, we can expect the situation to continue to get exponentially worse. He continues to deny the severity of the virus.

The White House science office announced this week that among Trump’s accomplishments are “ending the pandemic.” Stanford University researchers reported this week that Trump’s “superspreader” rallies in the summer through September 22 resulted in at least 30,000 infections and 700 fatalities. And that is before his own diagnosis, and his ramping up the frequency of the rallies through election day.

If Joe Biden is elected, there will still be 70 days before he takes office, and things can get much worse in that time.

We don’t have the luxury of waiting. A President-Elect Biden will need to use all the moral and political authority he can wield to get politicians and citizens to fundamentally change the way the nation is responding to the pandemic. And to recognize that all the other crises, from economic to mental health, derive from the failure to respond effectively to COVID-19.

Foundational Principle of Crisis Response: Take Risk Seriously

A foundational principle of crisis response is to understand the scope and specifically the risks that a crisis represents, and then to do all that is necessary to mitigate those risks. The longer it takes to do that, the worse the crisis will get.

Trump never took the risks seriously, at least in public. As early as February and for months after, he told Washington Post associate editor Bob Woodward what he knew about the virus:

- It is spread in the air.

- You catch it by breathing it.

- Young people can get it.

- It is far deadlier than the flu.

- It’s easily transmissible.

- If you’re the wrong person and it gets you, your life is pretty much over. It rips you apart.

- It moves rapidly and viciously.

- It is a plague.

But he was telling the nation the opposite.

The Washington Post has documented the scope and frequency of Trump’s lies while president: In his first 827 days in office, he told 10,000 lies or false statements, he told 10,000 more in the next 444 days. By July 2020, he was averaging 23 lies or false statements per day. By mid-October, it was more than 50 every day.

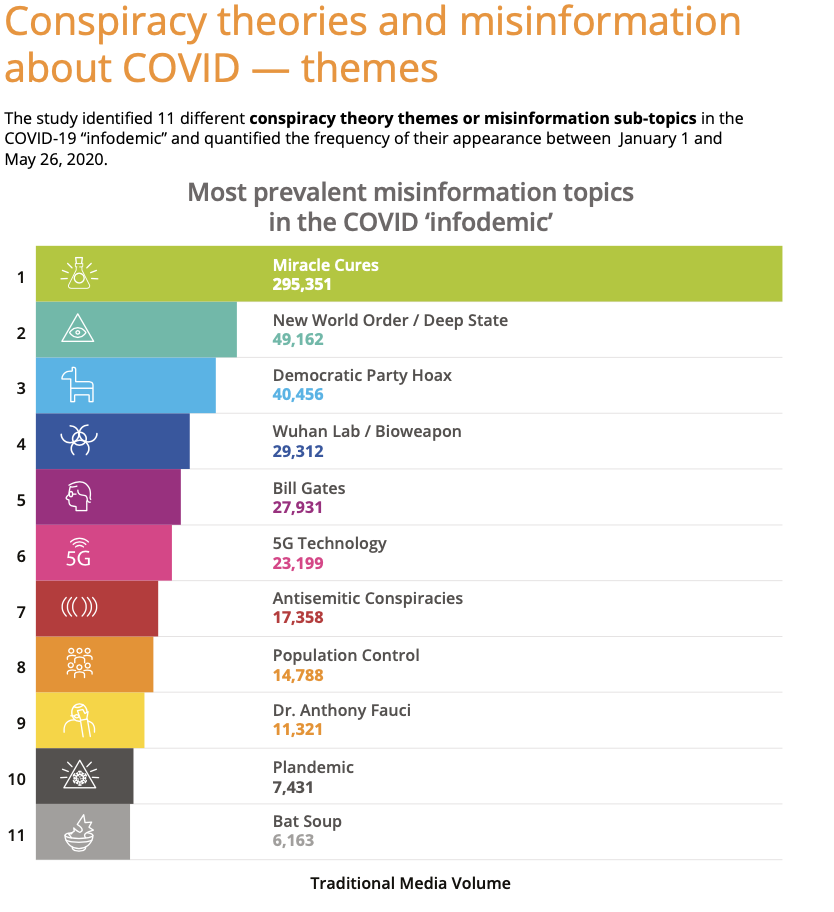

Last month Cornell University’s Alliance for Science published the first comprehensive study of COVID-19 misinformation in the media, and concluded that President Trump is likely the largest driver of the such misinformation.

And that misinformation had consequences. An analysis in mid-October by Columbia University’s National Center for Disaster Preparedness concluded that between 130,000 to 210,000 American fatalities would have been avoided if the nation had consistently applied policies equivalent to what other developed democracies had done. (Note that South Korea and the United States had their first cases on the same day. Our death rate is 78 times theirs.)

Columbia University, National Center for Disaster Preparedness

Advice from a Crisis Manager

I don’t have Joe Biden’s ear. But if I did here’s what I’d tell him and his team:

1. Create a true whole of government response.

We have never had a whole of government response, unlike most of our peer countries. Even at the federal level, we’ve had a fragments of government response. Different parts of the federal government had conflicting policies; political appointees micromanaged what had previously been independent agencies; there was inconsistency over time. And the states have been left to figure it out on their own.

Where Biden and his team don’t have authority (before inauguration, with states, cities, and counties), use persuasion and call for clear, consistent, and consistently-implemented policies and practices to stop the spread, treat the people, and treat the consequences of the poor response.

2. Immediately call for full implementation of the Defense Production Act.

Call for surging the manufacturing of ventilators, medical supply, testing equipment, personal protective equipment, and sanitization technologies.

Although President Trump has invoked the act in limited ways – to require meat processing employees to work in violation of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines, and for limited amounts of masks and testing equipment, he has not surged supply.

In July, the soon-to-retire head of the Defense Production Act program at the Federal Emergency Management Agency lamented that there was no national strategy: “Why isn’t this administration using the act to prevent shortages?”

A former legal advisor to the National Security Council concluded that, “What the federal government — the president or secretaries possessing delegated authority — have not done yet is use the D.P.A. to create a permanent, sustainable, redundant, domestic supply chain for all things pandemic.”

3. Call on all governors, mayors, and other executive branch leaders to implement a national masking, social distancing, and contact tracing policy.

Masks save lives and slow the spread of the virus. Of the 105 counties in Kansas, only 21 have mask mandates. A study last month by the University of Kansas found that counties with mask mandates saw a plateau of new cases at 20 per 100,000 people. But counties without mask mandates saw a serious spike in new cases to 40 cases per 100,000 people.

Similarly, a Vanderbilt University study last week concluded that hospitals with fewer than 25 percent of patients from counties with mask mandates had a surge in COVID-19 hospitalizations; hospitals with more than 75 percent of patients from counties with mask mandates saw essentially no change in COVID-19 hospitalizations from July to late October.

Finally, a University of Washington Study published in Nature Medicine says that up to half a million Americans could die of the virus in the next four months, but that up to 130,000 of them could be saved if 95 percent of Americans wear masks consistently in public.

4. Call on Congress to provide financial relief to states, businesses, families, and healthcare institutions.

The economic crisis is a direct result of mishandling the public health crisis. Now it isn’t just families and small businesses at risk, but also states, which are required to balance their budgets. States may need to cut essential services at precisely the moment when they will be most needed to keep people safe. And health care institutions are stretched thin and need assistance.

The next round of stimulus relief has been stalled because of election-year dynamics. But a clear Biden win and changes in the House and Senate could provide an opportunity to accelerate support.

5. Offer free testing

Knowledge is power. The availability of testing is still spotty and its reliability not clear. Biden should call for an army of testers, contact tracers, and managers to coordinate universal access to testing, an infrastructure to process tests quickly and reliably, and a further infrastructure to provide timely notice, notification, and referral to medical care when needed.

6. Respect science.

Restore true independence to CDC, FDA, HHS, and other public health operations of the US government. Take the advice of the science/public health experts to guide policy choices.

Public health should not be political. But the COVID-19 response has been highly-politicized. In a post-election environment, there is an opportunity to reset expectations and to get and follow the best advice of the scientists and public health experts.

It is the nature of science that it is self-correcting. When scientists are grappling with new challenges, they adapt understanding to what the evidence and data show. That should not lessen support for science, but actually increase it. Science isn’t dogma.

One of the first challenges post-election is whether, when, and how to go to a national shelter-in-place order similar to what some states did in the Spring. Britain just established a month-long lockdown. The decision on whether, when, how, and for how long to do something here should be based on the science and on the actual risks we face, not on political calculation.

7. Assure Americans’ access to healthcare.

One week after the election the U.S. Supreme Court will hear a case in which the U.S. government and state attorneys general will ask the court to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Despite Trump’s promises for months that a plan for better healthcare will be revealed “in two weeks,” there is no evidence of such a plan. Biden and his team must act quickly to create an alternative if the Court should nullify the healthcare that so many Americans rely upon.

In the meantime, the federal government should subsidize COVID-19 prevention, treatment, and recovery for the uninsured or underinsured.

These are not political recommendations: they’re crisis management recommendations based on the severity of the risks. The tragedy is that taking the risks seriously when Trump first knew about them could have prevented all of this suffering.

Leadership courage matters.

Companies without a pandemic crisis plan in place can still identify potential impacts to guide their response. Enterprise-wide impact mapping and assessment can help an organization prioritize next steps. By

Companies without a pandemic crisis plan in place can still identify potential impacts to guide their response. Enterprise-wide impact mapping and assessment can help an organization prioritize next steps. By  Similarly, companies that

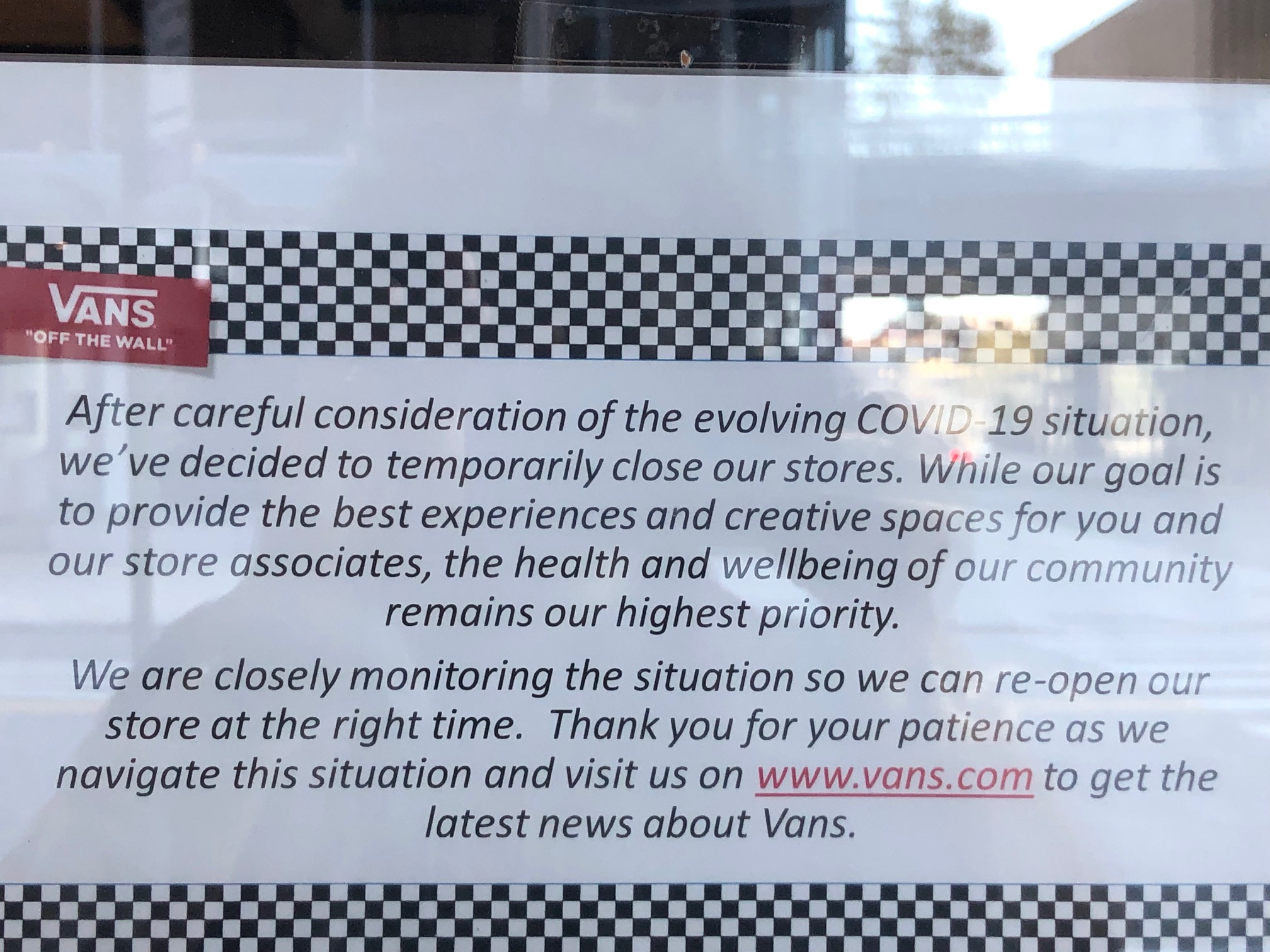

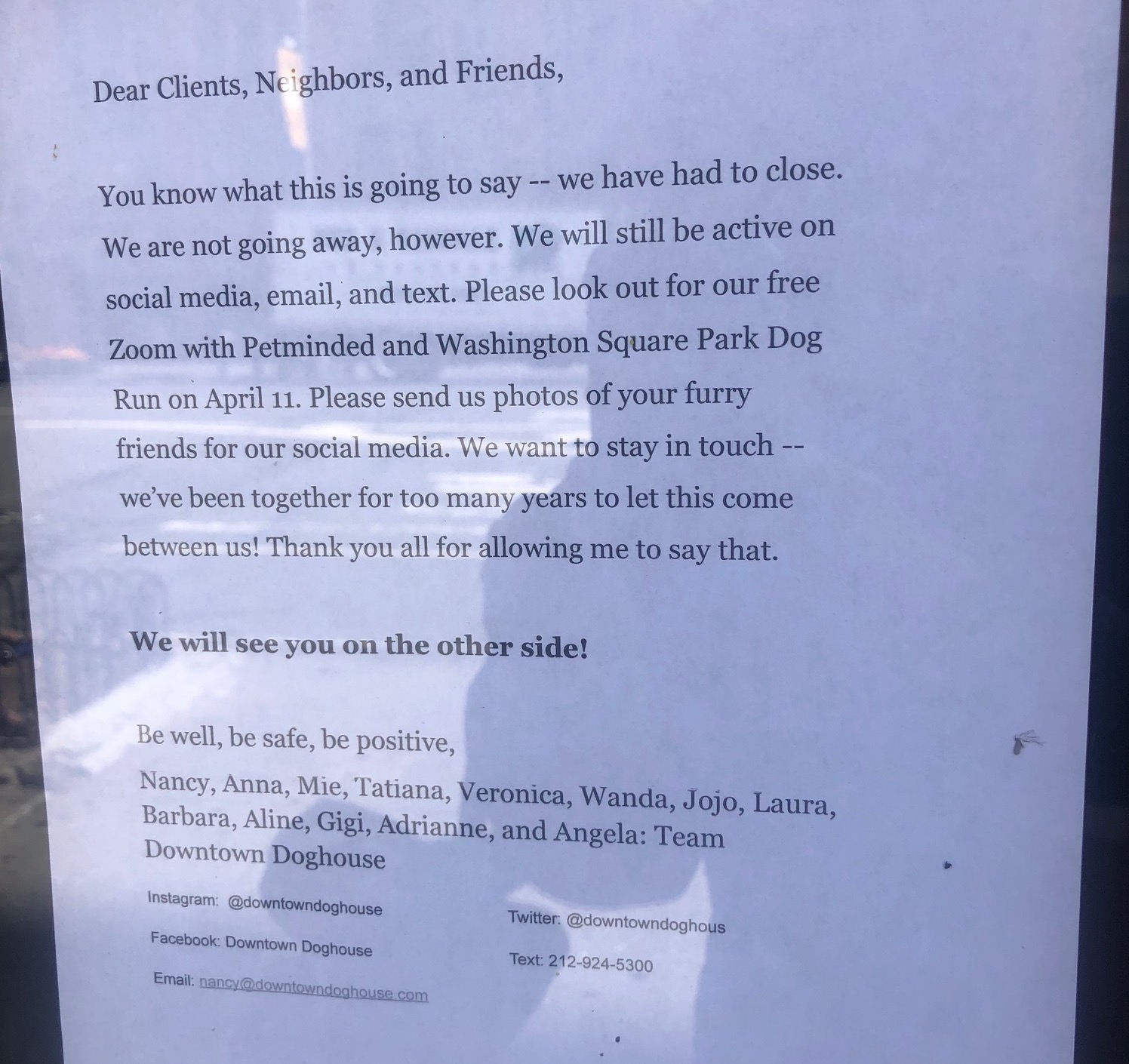

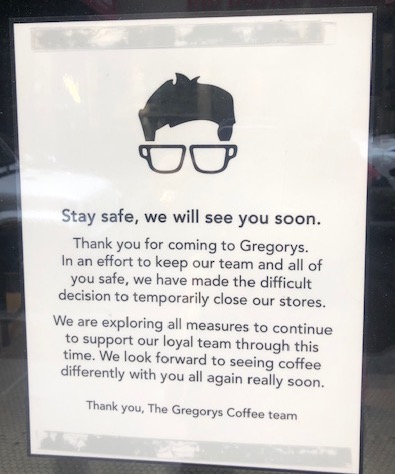

Similarly, companies that  On my first trip to the grocery store after a statewide “stay-at-home” order had been issued, the store had placed limits on the number of scarce items that customers could buy, like cleaning products and milk. Employees were working hard to keep shelves stocked. Two weeks later, consistent with evolving public health guidance, the store was limiting the number of customers allowed inside at once, plexiglass shields had been placed between checkout workers and customer payment stations, and all store employees wore gloves and masks. The grocery chain had also adopted an industry-wide practice reserving its opening hour for elderly customers. On my most recent shopping trip, the store had instituted “one-way” aisles to ensure physical distancing and all customers were required to wear face coverings.

On my first trip to the grocery store after a statewide “stay-at-home” order had been issued, the store had placed limits on the number of scarce items that customers could buy, like cleaning products and milk. Employees were working hard to keep shelves stocked. Two weeks later, consistent with evolving public health guidance, the store was limiting the number of customers allowed inside at once, plexiglass shields had been placed between checkout workers and customer payment stations, and all store employees wore gloves and masks. The grocery chain had also adopted an industry-wide practice reserving its opening hour for elderly customers. On my most recent shopping trip, the store had instituted “one-way” aisles to ensure physical distancing and all customers were required to wear face coverings.