Helio Fred Garcia | Bio | Posts

Helio Fred Garcia | Bio | Posts

31 Dec 2014

Every year I look for great moments in leadership and leadership communication. This year offered many candidates for the greatest leadership moment. The usual suspects come from the world of politics, sports, or business. But there was one unlikely moment in 2014 that in my view shows leadership in an unexpected light, one that offers both teachable moments and hope for leaders in any field.

Great Leaders Transcend the Either/Or

Ever since the murder of an unarmed black teenager in Ferguson, Missouri in August, there has been a growing movement calling attention to the disproportionate number of black youths who are killed by police officers. In the months following the Ferguson shooting, other police-involved shootings led to national protests, including the “Hands Up/Don’t Shoot” rallies and the Black Lives Matter movement.

The media has framed the conflict as police v. black communities, and New York City police have played into that dynamic by showing disrespect to New York Mayor Bill De Blasio after he noted that he has spoken with his own son, who is black, about his personal risk when interacting with police.

But however convenient for the media to paint the conflict as either/or; as pro-police or pro-community, it doesn’t have to be this way. And great leaders can transcend the bifurcation and find ways to unite and move forward.

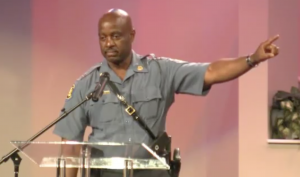

My pick for the best leadership and leadership communication moment in 2014 is Missouri Highway Patrol Captain Ron Johnson. I’ve taught his case in several graduate business and communication courses in the five months since, and each time it brings tears to the students’ eyes. I share it here.

Ferguson

Michael Brown was killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri on Saturday, August 9. The police mishandled the investigation and aftermath, and by midweek the St. Louis county and other local police forces mishandled the protests that erupted. The US and national media descended on the scene, broadcasting live from the streets.

The police over-reaction included paramilitary police in military gear riding on an armored vehicle, with a sniper aiming his rifle at protesters. It included tear-gassing of the crowds and of journalists, and intimidating journalists and other observers. The scene was reminiscent of a war zone, and covered that way in the national and international press.

The police over-reaction included paramilitary police in military gear riding on an armored vehicle, with a sniper aiming his rifle at protesters. It included tear-gassing of the crowds and of journalists, and intimidating journalists and other observers. The scene was reminiscent of a war zone, and covered that way in the national and international press.

By late week, Missouri governor Jay Nixon took control of the situation, and named the Missouri Highway Patrol as the agency responsible for crowd control. He appointed State Patrol Captain Ron Johnson the commander on the scene.

Johnson, who is black and who grew up and still lives in the Ferguson area, immediately reframed his role: it was not to protect Ferguson from the protestors, but to protect the protestors’ right to peaceably assemble.

The Transforming Moment

But the great moment in leadership came the Sunday eight days after Michael Brown’s shooting, and four days after the tear-gassing in the streets. It was at a church, at a rally in support of the Brown family. Capt. Johnson arrived wearing his state trooper uniform. There was palpable tension in the large crowd as he took the pulpit.  But he began in an unexpected way:

But he began in an unexpected way:

“I want to start off by talking to Mike Brown’s family. And I want you to know my heart goes out to you. And I say that I’m sorry. I wear this uniform. And I should stand up here and say that I’m sorry.”

It was a remarkable moment. And the crowd was not expecting it. There was initial silence, then applause, which lasted for more than thirty seconds; the final fifteen of which included cheers.

In that moment Johnson transformed the situation. He connected with the community; he opened a valve that allowed pent-up emotions to be released, in a positive and constructive way. He spoke first to the people most directly affected, the Brown family. He expressed sympathy for their loss, and then said he’s sorry. He repeated it in the frame of his uniform. Their experience of the police, from the shooting of their son to the mishandling of the crime scene to the bungling of the protests, was one of indifference and of confrontation. Here was a police leader moving past those experiences and connecting at a human level.

And there was significance in his phrase: “I wear this uniform. And I should stand up here and say that I’m sorry.” He was the first law enforcement officer to say so.

Having established an institutional leadership role, he then connected more personally, and made a personal commitment.

“This is my neighborhood. You are my family. You are my friends. And I am you. And I will stand and protect you. I will protect your right to protest.” (More cheers.) I’m telling you right now I’m full right now. I came in here today and I saw people cheering and people clapping, and this is what people need to put on TV.” (More cheers and applause.)

He then told his own story.

“When this is over, I’m going to in my son’s room. My black son. Who wears his pants sagging; wears his hat cocked to his side; has tattoos on his arms. But that’s my baby.”

Then he moved from the personal to the public:

“Let’s continue to show this nation who we are; continue to show this country who we are; for when these days are over Mike Brown’s family is still weeping, and they’re still praying…

He closed by connecting, promising, and rallying:

“I love you. I stand tall with you. And I’ll see you out there.”

A police officer told the community that he loves them. Remarkable.

Watch the six minute talk here:

Leadership Best Practices

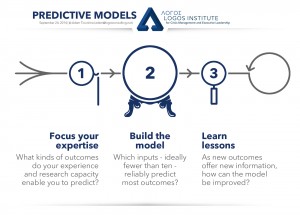

Capt. Johnson’s six minute talk met many of Logos Institute’s best practices. One is that you can’t move people unless you meet them where they are. Capt. Johnson did that, connecting in his first sentence with the Brown family and throughout with the community, both black and white. He understood the power of framing: “I wear this uniform. And I should stand up here and tell you I’m sorry.”

Our friend and fellow crisis counselor James E. Lukaszewski describes a pattern in crises he calls the Victim Cycle. Early intervention can pre-empt or shorten the victim cycle. In the early phases the victims (both those directly affected and those who empathize) need assistance with their own grief; to hear an expression of regret; to see involvement from the institution in queston; to receive information; and to have their plight recognized. In later phases they also need to receive validation of their suffering; get honest communication from the organization; to hear an apology from the top of the organization; to experience direct communication; and receive compassion. Capt. Johnson delivered all of those in his remarks.

And the Logos Institute best practices decision criteria were also met. The defining question in determining what to do or say is:

What would reasonable members of the stakeholder group appropriately expect

a responsible organization or leader to do when facing a situation like this?

And in the case of the Ferguson community, when Capt. Johnson addressed them, the reasonable expectations of a responsible leader would be to connect, express sympathy and regret, and to honestly declare his values, commitments, and next steps. Capt. Johnson did.

In many ways he was the leader best suited to do so.

Time magazine quotes St. Louis Police Chief Sam Dotson, who knows Captain Johnson from working on large events such as a presidential motorcade:

“He’s a quiet guy, but he is professional. When he speaks, people listen. When he acts, people respond to it. He’s familiar with the area, he comes from the area, and he connects with the community.”

Time quotes his former boss, Patrol Superintendent Colonel Roger Stottlemyer, who promoted Johnson to captain in 2012:

“I think he’s a calming influence on people. I think he knows the people there, he knows what their concerns are, he can relate to them having come from that community.” …Stottlemyer said that at the time Johnson was rising in the ranks, there were fewer than 100 officers of color in a force of 1,200 officers. “He was a star, and it was obvious from the beginning.” Stottlemyer said he promoted Johnson to Captain partly because he was impressed with his leadership style. “I observed when he was a corporal and a sergeant, the way he handled his men and the way he handled issues that comes up,” he said. “He communicates well with his people. He was an officer that you didn’t have complaints about.”

Unfinished Business

The national debate set off by the Ferguson killing and aftermath is bigger than any one local community and any one law enforcement officer. And however effective a leader Captain Johnson may be, the national controversy is large and getting larger, and many other players are now involved. The media continues to portray the issue as either/or; as police v. community/community v. police.

But in all the controversy, it is reassuring to see real leadership in action, even in a small community, that transforms a situation and brings people together. For his courage, his compassion, his authenticity, and his effective leadership, I am pleased to pick Capt. Johnson’s remarks on August 17 as the leadership and leadership communication moment of the year.

Your thoughts welcomed.

Fred