by Iris Wenting Xue

Last month, my mentor and boss, Helio Fred Garcia, and I visited more than 20 organizations, including top universities and prestigious corporations, in Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, and Tianjin.

During our visit, we have experienced different learning approaches and different cultural styles of lecture attendants. We had international students from joint-venture universities; Chinese students at top Chinese universities majoring in business (both MBA and Executive MBA), communication, and other liberal arts and sciences; senior PR managers from multinational groups; mid-career bankers from a national banking commission; and officials from local governments.

This post is the second in a series of posts on how to understand and overcome sociocultural obstacles. I learned three lessons about sociocultural and linguistic gaps during the Logos The Power of Communication China trip. In my last post I described the first gap: different languages. We can easily bridge the language gap by translation.

Today I will describe lessons about two other gaps that are harder to solve, although we constantly talk about them.

Lesson 2: Different Learning Approaches

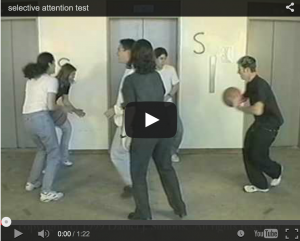

In order to demonstrate how hard it is for audiences to pay attention, we showed many of our audiences the video Invisible Gorilla. You can click on it and watch before you keep reading. You will be surprised about your counting skills.

I first watched this video during my strategic communication course at New York University in the Public Relations and Corporate Communication Graduate Program.

In this 30-second video, six people – three in white shirts and three in black shirts – pass basketballs around. The task for the audience is to count the number of passes made by the people in white shirts, and spot a gorilla that strolls into the middle of the action, thumps its chest and then leaves.

At that time I had a robust discussion with my classmates about 1) why was it so hard to accurately count how many times the players passed the basketball and also to spot a gorilla among human beings, 2) how to understand cognitive tunneling, which is what makes the tasks so hard, and 3) what we could learn and apply to our work from that exercise.

This time in China, I discovered some interesting learning approaches beyond these three takeaways – each specific to different groups of people.

1) PhDs

When we showed this video to a group of, let’s say, 50 people, there were always 15 who counted accurately, 10-ish who came close but got the number wrong, 10-ish who got close but chose a different number, 7-ish of some less-close number and two or three people who counted very wrong.

So one of our conclusions was “Counting numbers under 20 is not as easy as we thought it’d be.”

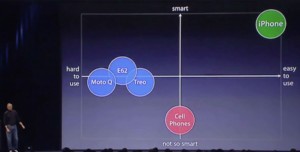

However, when we showed the video to a group of people including Ph.Ds in China, one of their conclusions was: “The answers could be plotted as a curve.”

This was the first time we discussed The Invisible Gorilla with PhDs. And this was the first time we received a response with the word “curve.” So, we responded with their language, “Gaussian distribution,” to acknowledge their worldview, to motivate them, to deepen the conversation.

2) Bankers

After the count, we typically asked: “While you were counting how many times the players passed the basketball, did you see a gorilla?” People either saw it or did not see it, so when they watched the video again they either were proud of their observation skills or disappointed that they had missed the gorilla.

We played the same video to a group of mid-career bankers. When we rewound the video, they denied that they had missed the gorilla:” We saw it, but we didn’t think it was a real gorilla. Instead, it was a human with a gorilla costume.”

This was the first time we had showed bankers The Invisible Gorilla. This was also the first time the audience challenged the content of the video. We respected the different habits, so we reframed the “gorilla” as “a human in a gorilla costume” based on their descriptions, to keep the conversation going.

3) Heads of Communications

Our routine at the end of the discussion was – “Any other thoughts and comments?”

Typically audiences will respond with their opinions about their counting skills or the missing gorilla.

But when we showed the same video to a group of PR directors, heads of public affairs and senior PR managers — from Standard Chartered, General Motors, Estée Lauder Companies, Coca-Cola, Dow Chemical Company and some other multinational enterprises — some of their final thoughts went far beyond the counting and the gorilla. Some of them knitted their brows and raised questions like “Are you manipulating us?”

They provided an interesting reason why the curve occurred, and why the gorilla, or the human with a gorilla costume, was overlooked. They insisted that the designer of the experiment manipulated the audience through putting a black gorilla among black-and-white-shirted players. They argued that since they concentrated on counting the passing of the white-shirt team, they could not pay attention to the black team and the black gorilla. If it had been a light brown gorilla, they would easily have dentified it.

How would you respond to this tricky question?

Lesson learned: “Understand your audience” appears in the slides we show to our clients. But we have to walk the talk and meet our audience by observing their approach and adopting their language.

Lesson 3: Different Cultural Styles

Before we landed in China, we thought we would face one group of audience – Chinese audience. To our surprise, our audience differed in certain ways: Some of them were shy but smart; some of them were as open like those in the States; some of them stayed in their own world, and it took us a long time to understand their thoughts.

I use the word “cultural style” to emphasize their subtle differences beyond imagination. To my surprise, I found in my research that Professor Dan Kahan of Yale Law School blogged this conception based on his study with his collaborators on Joseph Gusfield:

“The term “cultural style” is, for me, a way to describe these affinities. I have adapted it from Gusfield. I & collaborators use the concept and say more about it and how it relates to Gusfield in various places.…

Examples of these are cultural generations, such as the traditional and the modern; characterological types, such as ‘inner-directed and other-directed’; and reference orientations, such as ‘cosmopolitans and locals.’”

I agree with Kahan about how people differ from each other due to the difference of location or character and share the affinities with each other due to time or education background.

Below are the four main cultural styles during our trip:

1) Top Local University Style

We visited four of the top ten universities in China. Not to our surprise, the institutions are powerful. Here are some recent updates of some of them:

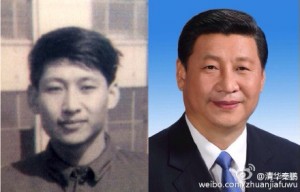

Tsinghua University celebrated its 104 anniversary this past Sunday and posted some old pictures of its famous alumni, including current President Xi (graduated from the School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department and later got an LLD degree), former President Hu (graduated from the Water Conservancy Engineering Department); the governor of the People’s Bank of China Xiaochuan Zhou (got a Ph.D. degree in Automation and System Engineering), and the controversial Chinese-born American Nobel Physics Prize winner Chen-Ning Franklin Yang (received a Master’s Degree and later became an honored director).

Xi Jinping, as a student at Tsinghua University, and now as President of China

Shanghai Jiaotong University, through its School of Media and Design (at which we spoke) and the University of Southern California jointly established The Institute of Cultural and Creative Industry (ICCI). Ernest J. Wilson III, Dean of the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, visited the same campus we visited one month after our visit.

To our surprise, some of their current students were not as vocal as we expected. Lectures we held in the top local universities were much more silent than those we held in joint-venture universities, although we discovered later that they had brilliant thoughts. In general, they are proud about being “blue blood”, and they tend to appear modest but think aggressively. They were reluctant to share their personal opinions about some topics until we pushed them several times.

2) Joint-Venture University Style

Elite universities in China and other countries are already on the path of exploring partnerships with universities from other countries. For example:

- In 2004, The University of Nottingham Ningbo China (UNNC) was set up by the University of Nottingham (UK) with the cooperation of Zhejiang’s Wanli Education Group in Ningbo, Zhejiang Province.

- In 2006, the Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (XJTLU) was jointly established by University of Liverpool and Xi’an Jiao Tong University in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province.

- In 2012, Duke Kunshan University was organized as a collaboration between Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, with Wuhan University, and the city of Kunshan, Jiangsu Province.

Among joint-venture universities we visited in China this time, we were impressed with New York University Shanghai, Johns Hopkins-Nanjing Center for Chinese and American Studies, and Sino-British College.

NYU Shanghai is NYU’s third degree-granting campus. Its enrollment started in Fall 2013, and now there are only Freshmen and Sophomores. Students are not only from China, or other Asian countries like Singapore, South Korea and the Philippines, but also from the States, Canada, France, Dubai and many other countries.

The Johns Hopkins-Nanjing Center for Chinese and American Studies is a joint educational venture between the School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University and Nanjing University. It has been operating in Nanjing since 1986.

Sino-British College is an international university college in Shanghai, China, jointly established by the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology (USST), and nine British universities (The University of Bradford, The University of Huddersfield, The University of Leeds, Leeds Metropolitan University, Liverpool John Moores University, Manchester Metropolitan University, The University of Salford, The University of Sheffield, and Sheffield Hallam University).

These three joint venture universities have built global classrooms with a global view, where students are open and comfortable hearing other opinions and sharing opinions themselves. The diversity of student and faculty kindled the diverse discussion we typically associate with academia.

3) Business Style (Communicators and Non-Communicators)

Business audiences tended to be more worldly and more serious. For example, when we talked about crisis management in a Corporate Social Responsibility Forum in Shanghai and showed a picture of an oil platform explosion to the communicators, participants immediately identified it as “BP”. It was self-evident. They were aware of what was happening in the crisis management field, even though they live in a country where people tend to whitewash scandals. Also, some of them asked tricky questions like “Is it a smart crisis strategy to find another crisis that will shift the focus and will thus save our company from the spotlight?”

Here is another sign of how seriously the business community takes professional development. When the largest residential real estate company in China (which has an office in New York) invited my boss, Helio Fred Garcia, to hold a speech about The Power of Communication, they not only offered a huge auditorium of 200 people, but also live broadcasted it to 40 other national offices. Each office was equipped with live broadcasted lecture and real-time slides. Each office had at least 20 attendants. And even though it was a Friday evening lecture, the company told us that they had an attendance rate of over 90 percent and that nobody left in the middle of the speech.

Executives at a Vanke regional office spending a Friday evening watching Prof. Garcia’s workshop via remote technology

4) Local Government Style

We coached 90 officials from Nanyang, a “small” city of 10 million residents in Henan Province.

They were being trained in crisis management because they were working on a huge national project “South–North Water Diversion”. (Think of the drought in California, and imagine diverting a major river 800 miles to California.) Due to this project, a huge amount of Nanyang residents had to relocate. So government officials were eager to be trained for if (or when) a crisis might happen.

Route of the Water Diversion Project to bring water from the South to the greater Beijing area

I did the simultaneous translation for the lecture. My observations are as follow:

- The officials were focused on the lecture, even though the majority of them cannot understand English beyond “Hello” and “Thank you”.

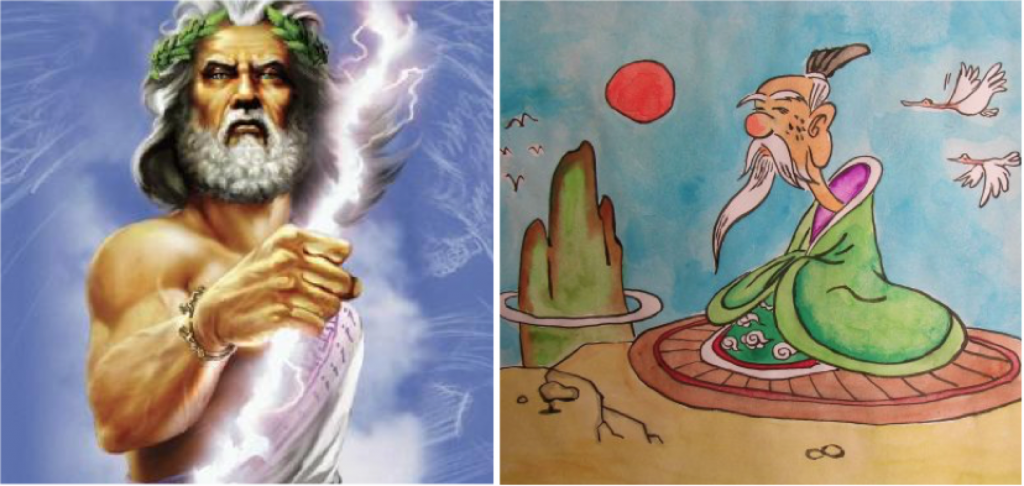

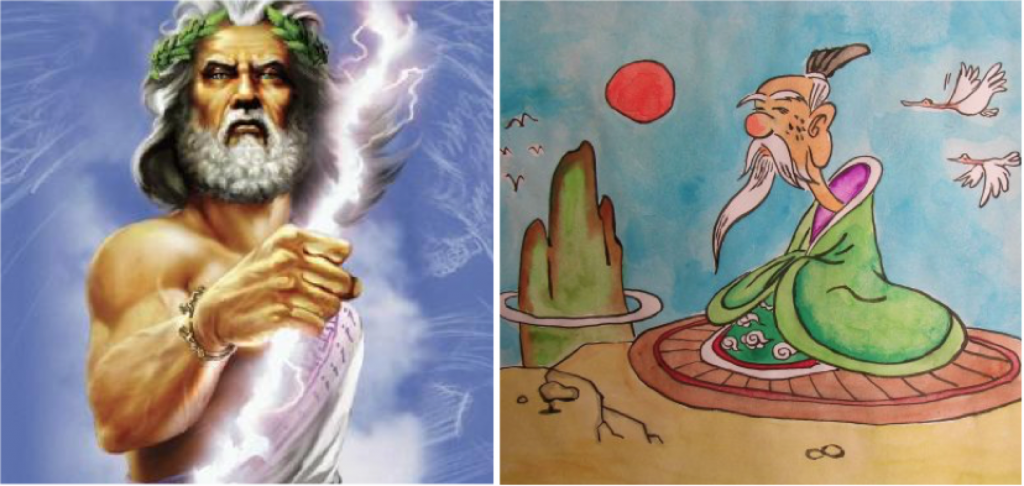

- They were the only group of people that were uniformly unfamiliar with Professor Garcia’s references to Greek tragedies. Every other group understood immediately when he referred Greek tragedies as the example that people remember bad things rather than good things. They were the only group of people that could not get our point of “Greek tragedies are all about choices — Do I kill my father and marry my mother?” Every other group, including students from universities and even engineers from big companies, laughed at the reference. The officials remained silent.

- They were eager to share a Confucius quote, and insisted that I translate it simultaneously for Professor Garcia. They also expected his response and feedback to the Confucius quote. In other words, they were the group who seemed to ignore others culture, but emphasize their own culture.

Zeus hurling thunderbolts; Confucius

Lesson Learned: When social patterns and cultural differences are involved, we have to be very careful about what is happening to people who do not share the same learning approach and same cultural style as ours.

The two lessons we learned today are much harder than the first lesson. Accordingly, there is no single solution for each of these gaps. But one large takeaway from the trip is that we need to take seriously not only differences in language but also differences in learning approach and cultural style.