Reflections on China

I have just returned from two weeks of teaching in China, and it has gotten me thinking.

I had prepared for the trip pretty pretty well — 150+ hours of one-on-one Mandarin lessons; several large books on Chinese history and politics; a 36-lecture audio course on Chinese history; and lots of review of Chinese media in English. But none of that made me ready for what I found there.

I come away with several large surprises, some observations (more about the US than about China), and some advice for my daughters, students, clients, and all others who want to make a difference in the world. (Short version: Learn Mandarin.)

All of that in a moment.

Why I Was There and What I Was Doing

I was in Beijing through Tsinghua University, recently rated the top school in China, as part of an exchange on crisis management among academics, business leaders, the government, and outside experts. The trip was funded by the International Distinguished Scholars program of the Tsinghua University Foundation.

Tsinghua just celebrated its 100th birthday. China’s president, premier, and many senior government officials are alumni. In addition to teaching its own students, Tsinghua also has executive education contracts with the government.

So my work involved teaching best practices in crisis management and crisis communication to both graduate students and government officials, as well as to groups of business and media leaders. Much of it was in the classroom. Some was beyond the classroom.

Surprises

I had the good fortune of spending lots of time speaking with and listening to people engaged in the current and future growth of China — in the classroom, at meals, in formal and informal settings.

Those discussions, my observations, and my reflection lead me to three surprises that can serve as organizing principles in my own understanding of China and its relationship to the United States and the rest of the world. They are:

- Scale

- Curiosity

- Optimism

A bit about each of these:

1. Scale

China is huge.

Its scale is breathtaking, almost impossible to grasp with an American frame of reference. The Chinese name for China is Zhongguo — literally the middle kingdom, the center of the world, or the center of civilization. Being there I can see why.

China has an uninterrupted history of nearly 5,000 years as a single civilization. In contrast, European settlement of the American hemisphere began about 500 years ago.

Beijing, with 19.7 million people, dwarfs New York, which has 8.4 million. Shanghai has even more: 23.3 million people. China has 160 cities with a population of more than 1 million. The United States has nine.

China has a landmass about the size of the US, but its population is the size of the US population plus another billion people.

The Great Wall, built by hand between 403 and 204 BC, was more than 1,200 miles long. Large portions still remain. I walked about five miles of it, and it continued well into and beyond the horizon. It seemed to go forever.

Walking for several hours through the Forbidden City, where emperors lived for hundreds of years, I thought I had covered the whole thing. Then I discovered that we weren’t even halfway through the compound, the biggest buildings yet to become visible.

Ceremonial meals seemed to go on without end — 15 courses or more, each one superb.

China has an old and venerable civilization and culture. But it’s also ultra modern. I was in Tianjin, a city about 100 miles south of Beijing, and had to get to a meeting back in my Beijing hotel.

We left Tianjin by train at 4. I was in my hotel at 5. The bullet train traveled the equivalent of Philadelphia to New York in 20 minutes. And the ride was smoother than any Acela I have ever ridden. A glass of water on the armrest would not have spilled.

The Beijing subway was modern, clean, well-lit, well-signed (in both Chinese and English) and easy to navigate. Also extremely crowded.

2. Curiosity

I was in China to teach crisis management best practices, which I teach in universities in the US and in Zurich. I expected the graduate students to be engaging. I was surprised by how curious, engaged, and engaging the government officials, business leaders, and media professionals were.

They seemed genuinely to want to master crisis management decision making. One of my core themes was the need to take stakeholder expectations seriously; to maintain trust and confidence by doing the right thing at the right time. I was surprised at how much this resonated with my audiences. I had expected the government to default to the desire to control information. I saw none of this. Instead, they seemed genuinely curious about how to win, keep, and build public trust, support, and approval.

I spent one morning teaching about 50 medical regulators, who had asked me to include social media trends among my topics. (I’m not expert in that, but I enlisted the States-side help of Laurel Hart, who heads Logos’ social media practice and who teaches social media at NYU and elsewhere.) I shared with the regulators how the US Food and Drug Administration uses social media – more than 10 separate Twitter accounts, YouTube, blogs, Flikr, etc. The regulators immediately moved from conceptual to operational questions: how do they do it; how many people work on it; how do they know what to put where, and when? I had expected something like “we can’t do that here.” Instead I got “how can we do that here?” I had similar reactions from other groups.

This curiosity takes many forms. China has a long history of absorbing ideas and best practices from elsewhere and incorporating them into a distinctively Chinese way of doing things. And there certainly seemed to be some of that going on. But I also detected a sense of urgency along with the curiosity. Some said directly that they knew they couldn’t control public opinion and had to earn it; some pointed to their own recent crises and noted how public support increased when the crises were well-handled and fell when the crises were mishandled.

But mostly I saw what we see in other environments of rapid change: anxiety about how to get ahead of an important trend. In this case, a recognition that in both the economic world and the political environment, control is unlikely to work as it once did, and now support must be earned. And a determination to learn how to earn that trust and support.

3. Optimism

China is on the rise.

Its GDP is growing at about 9 percent a year, according to the World Bank.

On average two new billionaires are coined every week. But China’s prosperity is not confined to the traditional elites: more than half a billion Chinese have emerged from poverty in the last 15 years, according to the World Bank. China is on an infrastructure and building construction boom.

I detected an energy in the streets — among the great masses of Beijingers — that I used to know in New York. And with everyone I spoke — high officials, the educated, and even taxi drivers and the waitresses in the hotel — a sense that this is a very good time to be Chinese. They seemed to be infused with a sense that, however rich and long their history, their best time was still to come.

I taught a group of non-Chinese graduates students at Tsinghua — students from the US, Canada, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, and India. I asked them why they were studying in China. They all gave the same reason: China is emerging as the land of opportunity. One of the American students put it this way: the American Dream is alive and well, but living in China.

Implications

Assuming that I’m on track about the scale, curiosity, and optimism I detected, we may indeed be in the early phases of what many have begun to call the Chinese Century.

China still has many problems and many challenges to overcome, and it’s still an open question how sustainable its economic growth can be or what kind of political system will ultimately emerge. But these are challenges China is aware of and grappling with. My prediction is that China ten years from now will be a more open and more prosperous society. Not necessarily in a George Soros- Open Society way, but in a distinctly Chinese way.

An ascendant China is not necessarily a threat to the US. While I was there US Vice President Joe Biden visited China, and he told audiences, according to China Daily:

“I believe that a rising China is a positive development. A rising China will fuel economic growth and prosperity, and will mean more demand for American-made goods and services and more jobs back home in the United States. It will also bring a new partner with whom we can meet global challenges together. It’s in our self interest that China continues to prosper.”

For my part, I think there are real opportunities for my firm’s US-based clients in China. Some, in finance and pharmaceuticals, are already very active there. Others are just beginning. But it’s a market with lots of potential for American companies.

The university with which I am most closely affiliated, NYU, is opening a full degree-granting campus in Shanghai next year. And my firm is likely to remain active in China. I’ve been invited back to Tsinghua in the spring to continue the work begun on this visit, and I’m now working to figure out the best way to make that happen.

Lessons: Learn Mandarin

Whether we like it or not, China will be a presence in our lives.

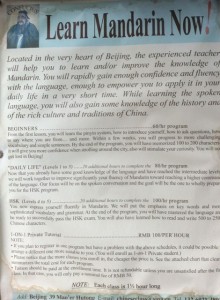

To become competitive we need to learn Mandarin, the single-most spoken language in the world. (It’s hard to learn, but I can recommend an excellent teacher.)

I’m convinced that in the coming decades knowledge of Chinese language will move from being a competitive differentiator to a basic necessity, much as in the 20th and early 21st centuries people outside the English-speaking countries learned English simply because it was expected for business, social, or academic advancement.

Americans typically pay little attention to the world beyond our shores. Our current political and economic conditions have led to a significant isolationist movement, from anti-immigration hysteria to the labeling of any economic good news abroad as a threat to our economic or national security. We need to get over it. China’s rise doesn’t equate to our demise (unless we make it so). But to remain competitive we need to be in relationship with China.

In my daughters’ and students’ lifetimes China will be a part of their daily lives.

One of the core crisis management principles I taught in China was the first-mover advantage: the sooner we do what we know we have to do, the more likely we are to succeed. My Tsinghua non-Chinese graduate students were already doing it: studying in China because that’s where the future is heading. We need to get ahead of that trend.

Thoughts, comments, critiques welcomed. I look forward to an ongoing discussion.

Fred

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!