How Obama Channeled Reagan and Washington in His Farewell

Last week’s viewers might have felt the president’s inclusiveness, but history will remember his dire warnings.

Ten days before handing the Oval Office keys to a successor famous for his mega-rallies, Barack Obama gathered one last huge crowd of his own. His January 10 farewell address was all about his 20,000 admirers at Chicago’s McCormick Place.

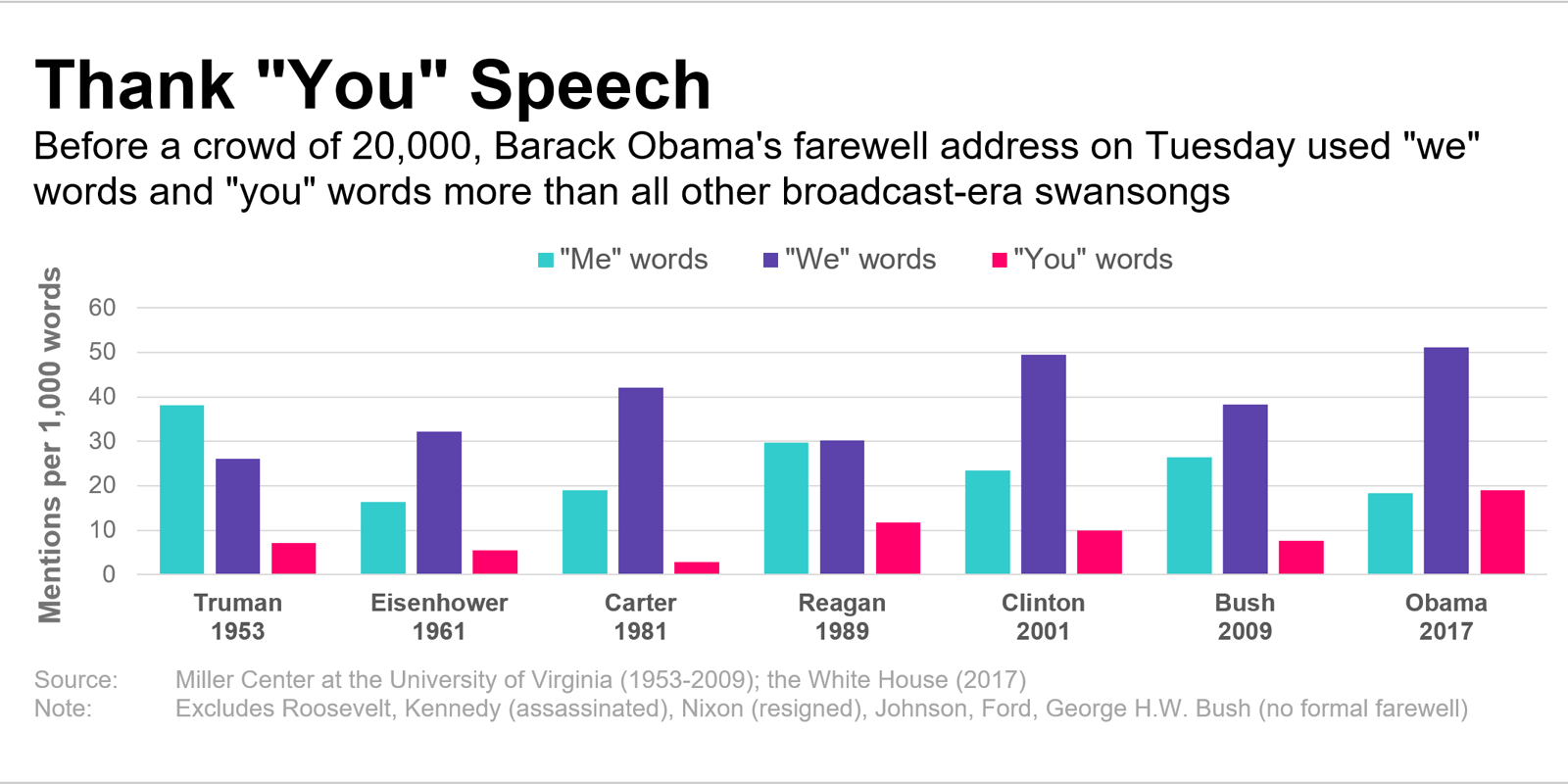

“You made me a better president,” Obama said, “and you made me a better man,” Over the course of his 4,267-word speech – the longest presidential farewell of the broadcast era – he used “you,” “your,” or “yours” 81 times. That’s 19 “you” words per 1,000 total words, besting Ronald Reagan’s 1989 mark of 12 per 1,000.

As with inclusive “we” words (like “we,” “us,” and “ours”), the use of “you” words is a hallmark of effective leadership communication. According to Quantified Communications CEO Noah Zandan, who studies and advises on public speaking, visionary leaders like Tesla’s Elon Musk and Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg use “you” words 60 percent more often than the average speaker.

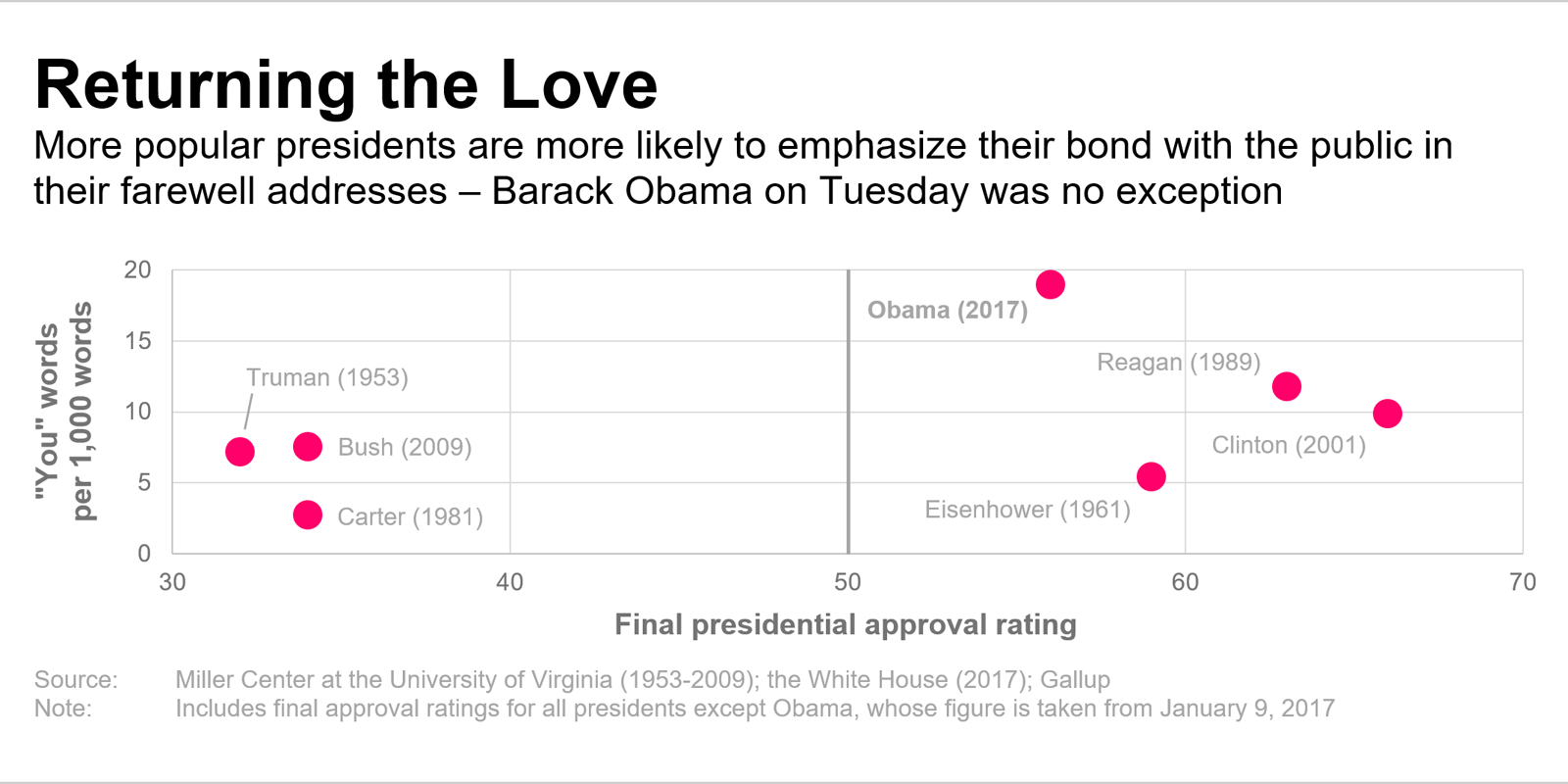

More popular presidents use more “you” words, too. Obama reflected the glow of his 56 percent approval rating in the latest Gallup tracking poll, ending a list of accomplishments by telling his audience, “That’s what we did. That’s what you did. You were the change.”

Reagan, who left office with a 62 percent approval rating and a nickname as “The Great Communicator,” did much the same in his farewell address. “I’ve had my share of victories in the Congress,” he said, “but what few people noticed is that I never won anything you didn’t win for me.” Reagan also laced the speech with vivid portraits of presidential life, putting watching Americans in his shoes. “You spend a lot of time going by too fast in a car someone else is driving, and seeing the people through tinted glass … And so many times I wanted to stop and reach out from behind the glass, and connect. Well, maybe I can do a little of that tonight.”

Among the seven farewell addresses of the broadcast era, there’s a clear correlation between the frequency of “you” words and the president’s final approval rating – tighter than the slightly positive relationship between “we” words and approval, or the slightly negative one between “me” words and approval.

“You” words are likely both a cause and an effect of the public’s thumbs-up. It’s possible that “you” words are a president’s response to high approval, as when Obama said, “You are the best supporters and organizers anyone could hope for, and I will forever be grateful.” Or, “you” words could be a driver of high approval, convincing voters that the president cares about them: “I am asking you to believe,” Obama said, “Not in my ability to bring about change, but in yours.” (Obama used the word “change” 14 times in his farewell address, echoing his final State of the Union last year and, most of all, his 2008 campaign.)

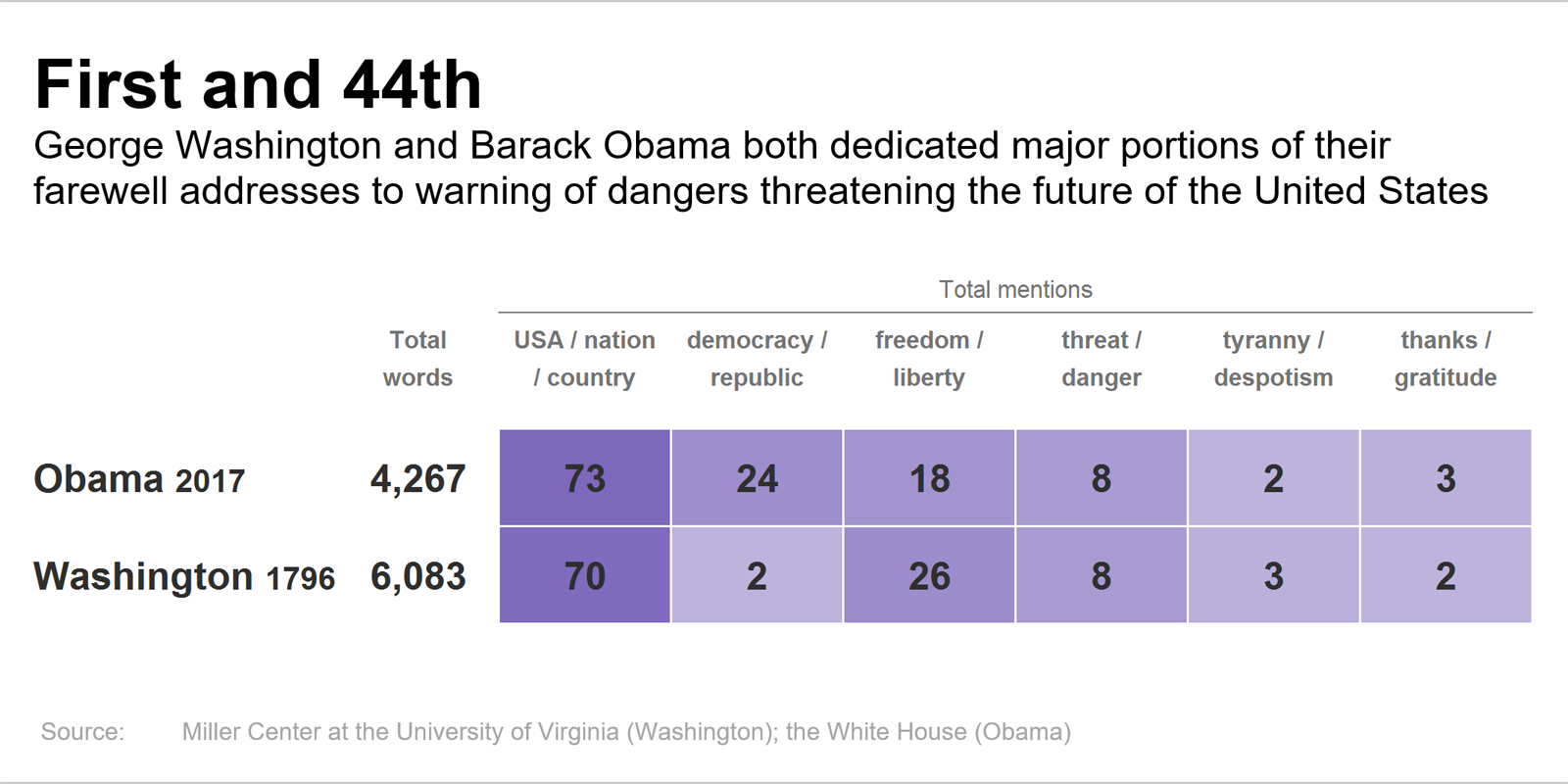

However, the part of Obama’s swansong that will most likely capture the attention of 22nd Century historians isn’t his inclusive tone. It’s when he drew on the mother of all precedents, George Washington’s hand-written 1796 farewell letter, to go from eulogy to sermon and back again. Bookended by a list of accomplishments and a list of thanks, Obama devoted the middle 57 percent of his speech to warning of three “threats to our democracy:” Economic inequality, racial division, and political partisanship.

“Democracy does require,” Obama intoned, “a basic sense of solidarity – the idea that for all our outward differences, we are all in this together.” Or, in Washington’s words, “You should properly estimate the immense value of your national union to your collective and individual happiness.”

The similarity wasn’t lost on Obama, who at one point even cited his source. “In his own farewell address, George Washington wrote that self-government is the underpinning of our safety, prosperity, and liberty, but,” Obama said, quoting Washington, “’from different causes and from different quarters much pains will be taken … to weaken in your minds the conviction of this truth.’”

The most famous phrase of any modern farewell address is a warning, too. Dwight Eisenhower coined the term “military-industrial complex” to warn of runaway defense spending as he left office in 1961.

For more, follow @Tiouririne on Twitter.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!