Humility Update: Humility is Strength. Obama Wins Nobel Peace Prize

The Paradox of American Power

Between the 9/11 attacks and the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, the foreign policy establishment focused on the difference between “soft power” and “hard power.”

The concepts were elaborated in a 2002 book by Joseph S. Nye, Jr., then dean and now University Distinguished Service Professor at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. Nye is consistently ranked one of the most influential US scholars on foreign policy.

His book, The Paradox of American Power: Why the World’s Only Superpower Can’t Go it Alone, was remarkably prescient.

Nye defines hard power as of the use of force, usually military, to coerce others in the service of a foreign policy outcome. Soft power consists of using all of the instruments of influence — diplomacy, cultural exchange, negotiation, persuasion — to get others to want to support a path of action to secure a foreign policy outcome.

Here’s the paradox of American power, as Nye defines it: the more one uses hard power, the more difficult it is to maintain international support for a policy position. Over time, hard power is depleted, and erstwhile allies become disillusioned. Soft power is usually far more effective in securing long-term security and stability. And with soft power, there’s always the option to escalate to hard power if necessary.

Or to put it in slightly different terms (not used by Nye): Bullying, however effective in the short term, is self-limiting and ultimately counterproductive. Persuasion is much more effective, especially over time.

Hard Power v. Soft Power: Bush v. Obama

This difference between coercion and persuasion can be seen as the fundamental foreign policy difference between the administrations of George W. Bush and Barack Obama.

President Bush’s approach was the unilateral use of force (including redefining appropriate levels of interrogation, use of secret detention facilities, and long-term deployment of the US Armed Forces). He gave only lip service to diplomacy — and even appointed a United Nations ambassador who was opposed to the very idea of the UN. (John R. Bolton, who became interim UN Ambassador on a recess appointment, famously said “There is no such thing as the United Nations. There is only the international community, which can only be led by the only remaining superpower, which is the United States.”)

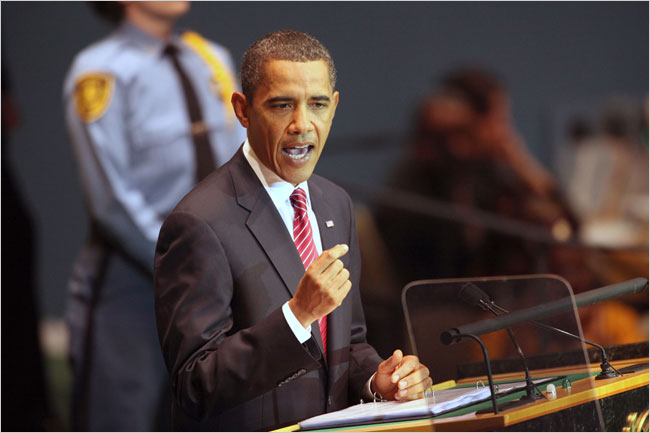

President Obama’s approach is to return to soft power as the primary instrument of US foreign policy, with hard power still in play (for now) in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Last month I posted how President Obama had won a major diplomatic victory in the UN and G-20 by rallying Britain, France, and even Russia to bring pressure on Iran, which led to Iran opening its newly-discovered nuclear facility for inspection by international observers.

Obama Wins Nobel Peace Prize

This morning the use of soft power was validated when President Obama, in a stunning surprise, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

In its award announcement, the Nobel Committee noted President Obama’s

“extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples. The Committee has attached special importance to Obama’s vision of and work for a world without nuclear weapons.”

Critics of soft power often deride it as sentimental or even dangerous. They assert that only force can protect US interests.

The Nobel Committee’s validation of soft power notes that multi-lateral engagement makes the world a safer place.

“Obama has as President created a new climate in international politics. Multilateral diplomacy has regained a central position, with emphasis on the role that the United Nations and other international institutions can play. Dialogue and negotiations are preferred as instruments for resolving even the most difficult international conflicts. The vision of a world free from nuclear arms has powerfully stimulated disarmament and arms control negotiations. Thanks to Obama’s initiative, the USA is now playing a more constructive role in meeting the great climatic challenges the world is confronting. Democracy and human rights are to be strengthened.”

In this blog I’ve argued that humility is strength, and that a dollop of humility tempers other attributes, and makes a leader even stronger. Humility helps a leader to recognize that maybe – just maybe – he or she might be wrong; that there may be other valid perspectives; that he or she doesn’t have to be the smartest person in every room, at every meeting.

Indeed, President Obama’s public statement responding to the award was one of humility, framing the award not as acknowledgment of past actions but as a momentum-builder for the course he has embarked upon. He sent an e-mail to Americans that said:

“This morning, Michelle and I awoke to some surprising and humbling news. At 6 a.m., we received word that I’d been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for 2009.

To be honest, I do not feel that I deserve to be in the company of so many of the transformative figures who’ve been honored by this prize — men and women who’ve inspired me and inspired the entire world through their courageous pursuit of peace.

But I also know that throughout history the Nobel Peace Prize has not just been used to honor specific achievement; it’s also been used as a means to give momentum to a set of causes.

That is why I’ve said that I will accept this award as a call to action, a call for all nations and all peoples to confront the common challenges of the 21st century. These challenges won’t all be met during my presidency, or even my lifetime. But I know these challenges can be met so long as it’s recognized that they will not be met by one person or one nation alone.

This award — and the call to action that comes with it — does not belong simply to me or my administration; it belongs to all people around the world who have fought for justice and for peace. And most of all, it belongs to you, the men and women of America, who have dared to hope and have worked so hard to make our world a little better.”

So today we humbly recommit to the important work that we’ve begun together. I’m grateful that you’ve stood with me thus far, and I’m honored to continue our vital work in the years to come.”

The humility expressed in that statement is not a sign of weakness, but of a mature self-confidence.

That mature self-confidence is what allows the new paradigm in US foreign policy, recognized by the Nobel Committee.

Persuasion has overtaken coercion as the instrument of national security. It’s a lesson for all leaders. And it’s an encouraging sign for all who take persuasion seriously, and for US interests abroad.

Fred

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!